|

||

|

||

Threat actors have been targeting vulnerable Redis instances since February 2022 when the Redis Lua Sandbox Escape and Remote Code Execution Vulnerability, also known as “CVE-2022-0543,” was discovered. The Mushtik Gang was one of the first cyber attack groups to exploit it. They infected vulnerable devices with a malicious script that allowed them to download files, inject shell commands, and launch flood and Secure Shell (SSH) brute-force attacks remotely.

Just last month, Palo Alto Networks’s Unit 42 uncovered another exploitation attack targeting the same bug, this time using a self-replicating peer-to-peer (P2P) worm they’ve dubbed “P2PInfect.” They published seven indicators of compromise (IoCs)—five IP addresses and two domains—as part of their analysis.

WhoisXML API expanded the list of P2PInfect IoCs and discovered that:

A sample of the additional artifacts obtained from our analysis is available for download from our website.

WHOIS lookups for the two domains identified as P2PInfect IoCs only produced results for one domain name—myhealthlifego[.]com. Created in October 2022, it was administered by PDR Ltd. and registered in China.

DNS lookups, meanwhile, for the domains identified as IoCs showed that myhealthlifego[.]com resolved to 66[.]154[.]127[.]38 (also identified as a P2PInfect IoC).

Next, a bulk IP geolocation lookup for the IP addresses identified as IoCs revealed that:

Reverse IP lookups for the IP addresses identified as IoCs showed that only one continued to serve as a domain host—66[.]154[.]127[.]38. It was dedicated to hosting the domain myhealthlifego[.]com.

Domains & Subdomains Discovery searches for the string worldive similar to one of the domains identified as IoCs turned up six similar-looking domains. None of them were categorized as malicious to date.

It’s also interesting to note that one of them—oneworldive[.]com—seemed to belong to a legitimate company as none of its WHOIS record details have been redacted. Additional Google searches, in fact, pointed to a legitimate and registered dive and travel company. They may have obtained the misspelled variation of their official domain name—oneworlddive[.]com—as an anti-cybersquatting measure.

Apart from determining P2PInfect DNS connections, we also sought to discover if threat actors could target Redis instances in other ways, such as via phishing and DNS takeover attacks. To do that, we used redis as a Domains & Subdomains Discovery search term for both domains and subdomains.

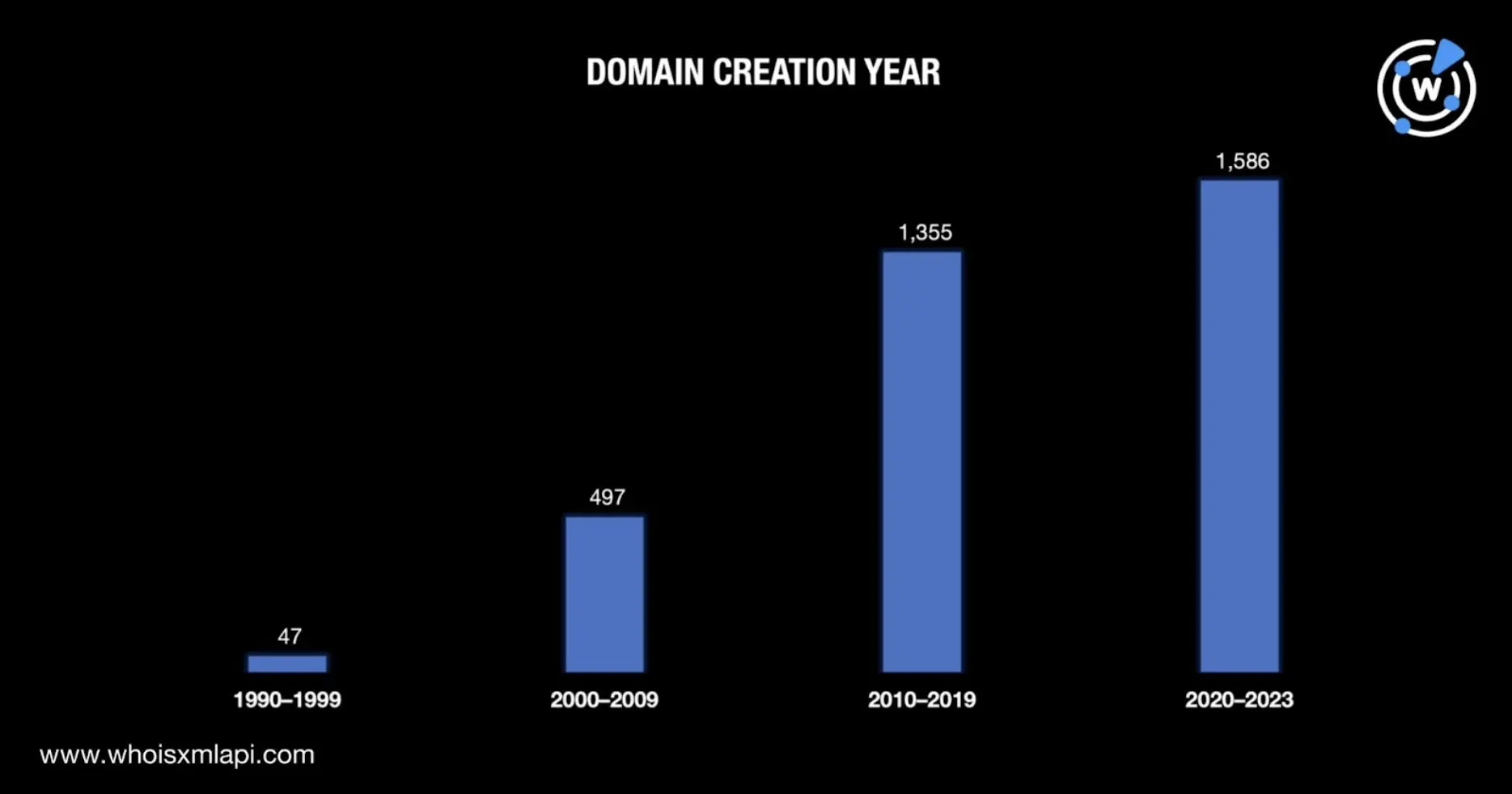

We uncovered more than 10,000 redis-containing domains.

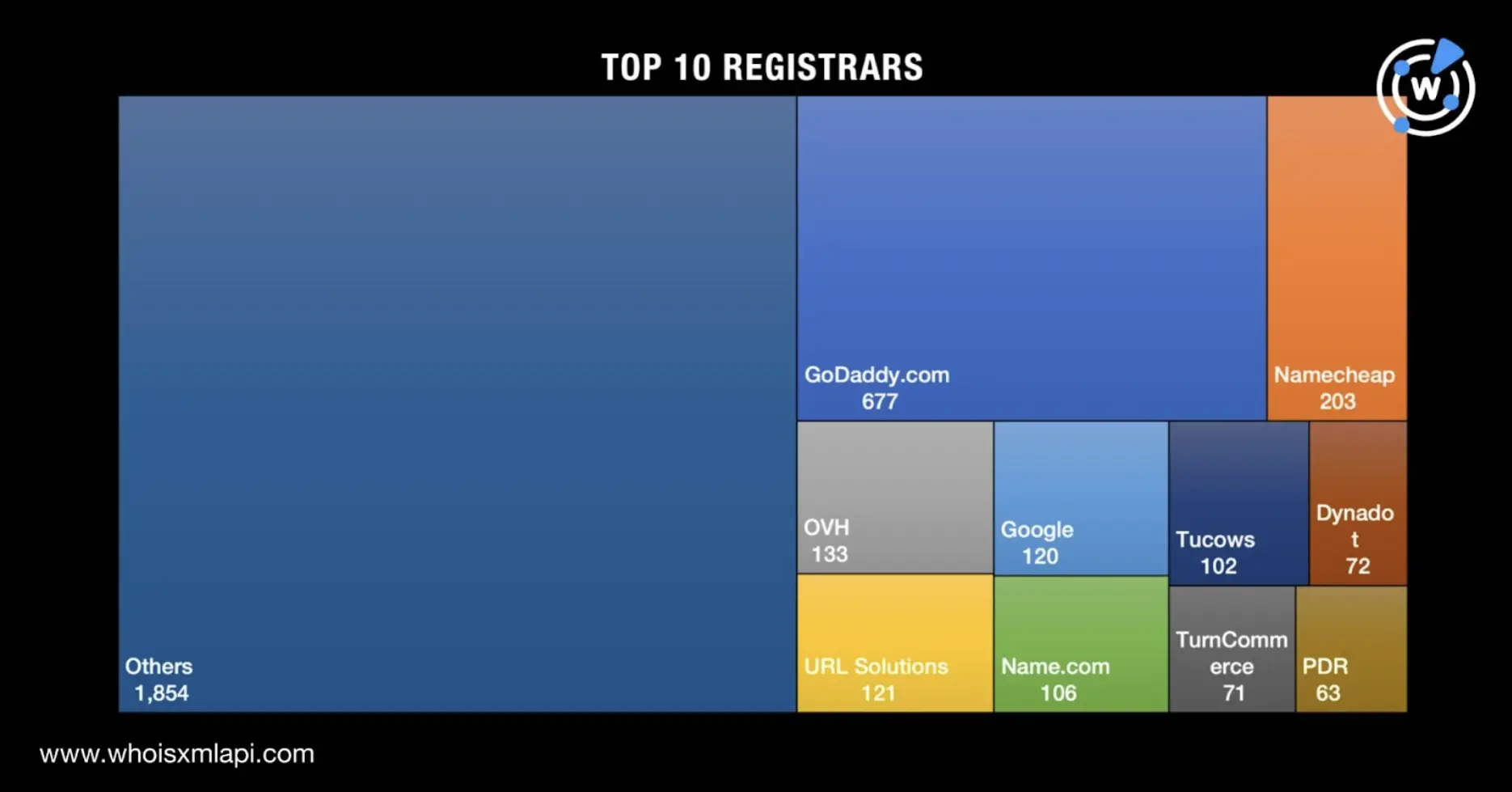

The 3,522 domains whose owners indicated their registrars were spread across 428 registrars led by GoDaddy.com, which accounted for 677 domains. Namecheap (203 domains), OVH (133 domains), URL Solutions (121 domains), Google (120 domains), Name.com (106 domains), Tucows (102 domains), Dynadot (72 domains), TurnCommerce (71 domains), and PDR (63 domains) completed the top 10.

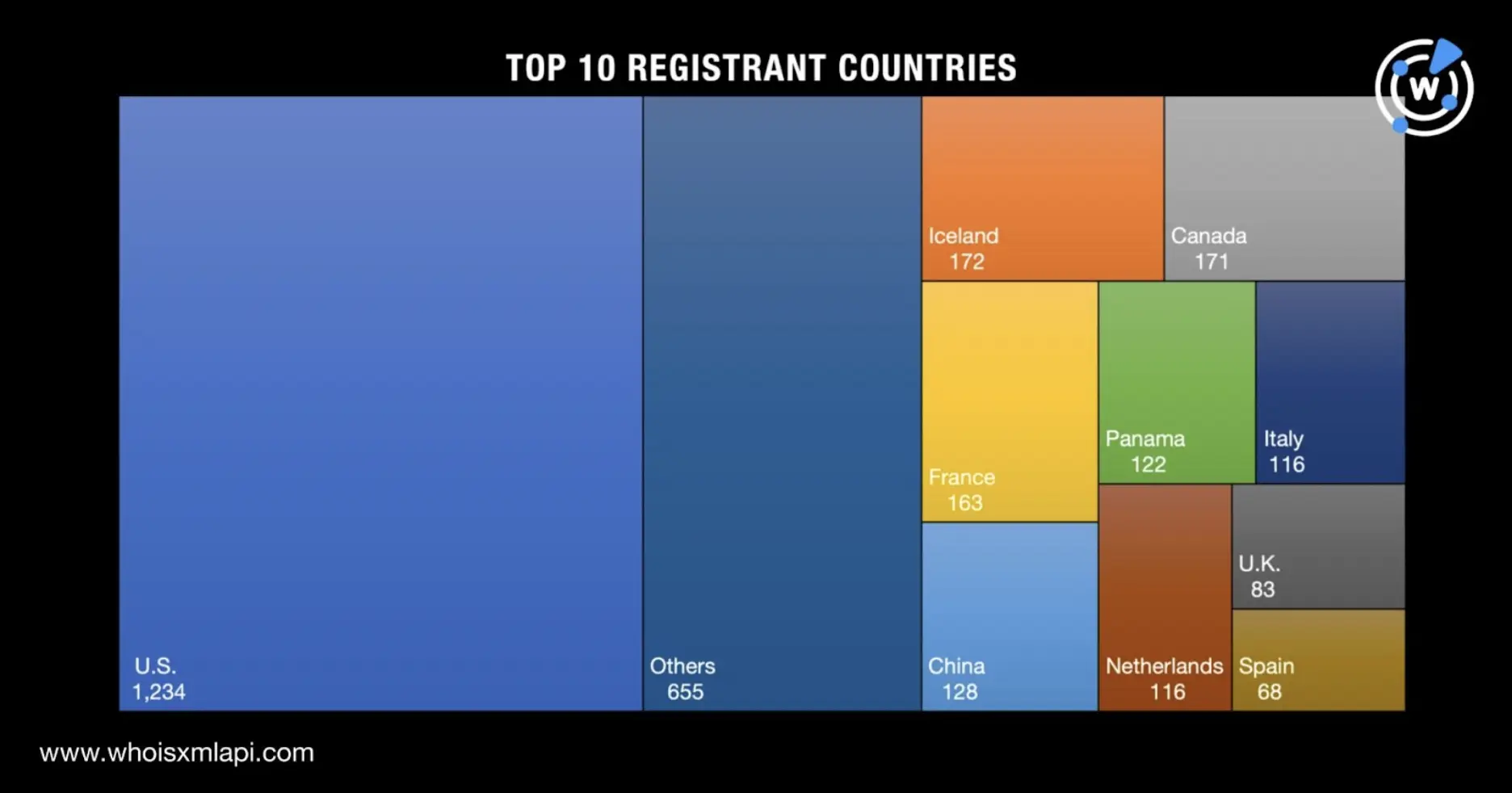

The 3,028 domains with unredacted registrant countries were registered in 95 countries led by the U.S., which accounted for 1,234 domains. Iceland (172 domains), Canada (171 domains), France (163 domains), China (128 domains), Panama (122 domains), Italy and the Netherlands (116 domains each), the U.K. (83 domains), and Spain (68 domains) rounded out the top 10.

A bulk malware check for the redis-containing domains showed that 20 of them were classified as malicious—17 as malware hosts and three as spam senders.

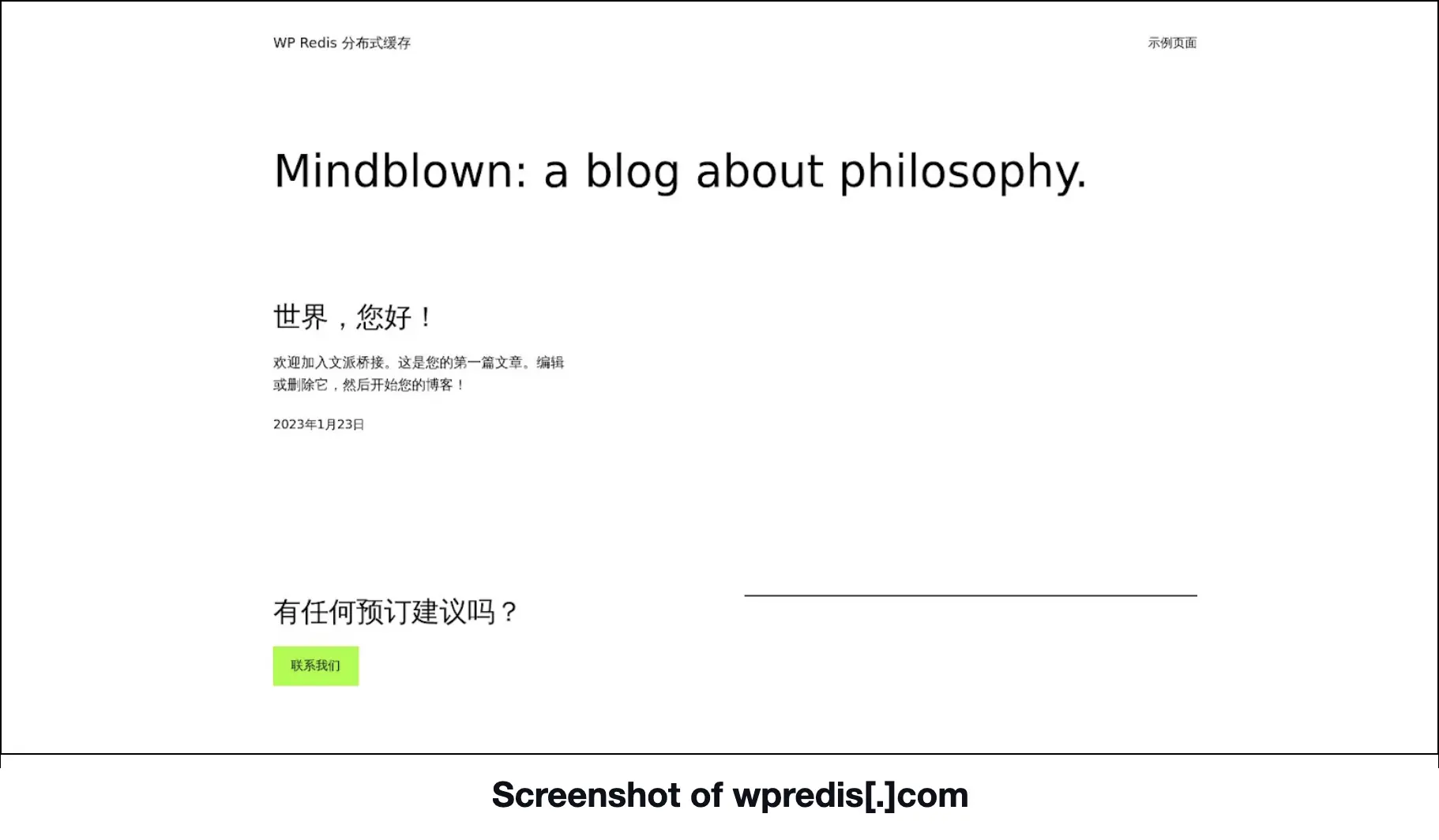

Screenshot lookups for the malicious brand-containing domains, meanwhile, revealed that seven of them remained accessible—two hosted live content, four led to error or blank pages, and one was up for sale. Of those that continued to host live content, wpredis[.]com proved most interesting in that based on the domain name alone, it could be confused for a WordPress-hosted blog on Redis devices. While it does host a blog, it doesn’t seem to have anything to do with the server.

Next, a bulk malware check for the redis-containing subdomains showed that six turned out to be malware hosts.

Finally, screenshot lookups for the malicious brand-containing subdomains revealed that three remained accessible—one continued to host live content and two led to error pages.

Our Redis vulnerability exploit attack IoC expansion analysis led to the discovery of other domains that looked similar to one of the domains identified as IoCs. Scouring the DNS, meanwhile, for domains and subdomains that threat actors may have already used or could potentially weaponize in future Redis-targeted attacks allowed us to identify 25 malicious web properties and close to 20,000 artifacts.

All that said, our DNS deep dive findings could point to more attacks trailing their sights on Redis devices although not necessarily via the already much-exploited Redis Lua Sandbox Escape and Remote Code Execution Vulnerability or CVE-2022-0543. Look-alike domains could figure in phishing campaigns while forgotten subdomains could serve as DNS takeover vectors.

If you wish to perform a similar investigation or learn more about the products used in this research, please don’t hesitate to contact us.

Disclaimer: We take a cautionary stance toward threat detection and aim to provide relevant information to help protect against potential dangers. Consequently, it is possible that some entities identified as “threats” or “malicious” may eventually be deemed harmless upon further investigation or changes in context. We strongly recommend conducting supplementary investigations to corroborate the information provided herein.

Sponsored byDNIB.com

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byWhoisXML API

Sponsored byRadix

Sponsored byCSC

Sponsored byIPv4.Global

Sponsored byVerisign