Poland thwarted a large-scale cyberattack on its energy grid without disruption, offering a rare case study in critical infrastructure resilience, decentralised energy governance, and the balancing act between openness and digital security.

Poland thwarted a large-scale cyberattack on its energy grid without disruption, offering a rare case study in critical infrastructure resilience, decentralised energy governance, and the balancing act between openness and digital security.

Telecom operators are challenging OTT platforms by deploying Rich Communication Services. This reversal of roles prompts fresh regulatory scrutiny, revives the case for network neutrality, and demands a risk-based approach to preserving digital competition.

Telecom operators are challenging OTT platforms by deploying Rich Communication Services. This reversal of roles prompts fresh regulatory scrutiny, revives the case for network neutrality, and demands a risk-based approach to preserving digital competition.

The international community has long struggled with the challenge of translating international law into actionable norms and practices in cyberspace. The conclusion of the United Nations Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG) on the security of and in the use of information and communications technologies 2021-2025 marks a vital milestone in that ongoing process.

The international community has long struggled with the challenge of translating international law into actionable norms and practices in cyberspace. The conclusion of the United Nations Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG) on the security of and in the use of information and communications technologies 2021-2025 marks a vital milestone in that ongoing process.

At the ICANN 81 meeting in Istanbul on 10 November 2024, I gave a presentation about the DNS Root Server System, in an effort to increase understanding of the Root Server System (RSS) and Root Server Operators (RSOs). The talk was intended for the members of the ICANN Governmental Advisory Committee (GAC), but much of this explanation may be of interest to general audiences.

The debate surrounding network usage fees in Brazil has intensified following the approval of Bill 469/2024 by the House of Representatives' Communications Committee in early December 2024. This bill prohibits telecommunications operators from charging internet companies based on data traffic. While this is merely a preliminary step in a lengthy legislative process, it signals that proposals from telecom companies to implement network usage fees are unlikely to gain traction.

The debate surrounding network usage fees in Brazil has intensified following the approval of Bill 469/2024 by the House of Representatives' Communications Committee in early December 2024. This bill prohibits telecommunications operators from charging internet companies based on data traffic. While this is merely a preliminary step in a lengthy legislative process, it signals that proposals from telecom companies to implement network usage fees are unlikely to gain traction.

In the wake of the election, sweeping policy shifts in the information economy are set to accelerate. Expect fast-tracked FCC reforms, Starlink subsidies, and AI-driven oversight to redefine media, tech, and regulatory landscapes. From relaxed antitrust to intensified media control, these eleven reversals signal a move toward deregulation and Chicago School libertarianism, with lasting impacts on U.S. markets and governance.

In the wake of the election, sweeping policy shifts in the information economy are set to accelerate. Expect fast-tracked FCC reforms, Starlink subsidies, and AI-driven oversight to redefine media, tech, and regulatory landscapes. From relaxed antitrust to intensified media control, these eleven reversals signal a move toward deregulation and Chicago School libertarianism, with lasting impacts on U.S. markets and governance.

At first glance, this book looks like another history of the Internet, but it is much, much more. The authors use their engineering and scholarly understanding of what constitutes Internet history to identify forks in the digital road and key past decisions that shaped the Internet's path. The first part of the book maps out the core technical and policy decisions that created the Internet.

At first glance, this book looks like another history of the Internet, but it is much, much more. The authors use their engineering and scholarly understanding of what constitutes Internet history to identify forks in the digital road and key past decisions that shaped the Internet's path. The first part of the book maps out the core technical and policy decisions that created the Internet.

On July 22, the FCC's open Internet order - which transforms Internet access service from a lightly regulated information service into a heavily regulated telecommunications service - will take effect. This article describes the policies and legal theories underlying the Order and the Order's effect on consumers of Internet services and providers of the service, including a number of entities that had previously escaped FCC regulation.

On July 22, the FCC's open Internet order - which transforms Internet access service from a lightly regulated information service into a heavily regulated telecommunications service - will take effect. This article describes the policies and legal theories underlying the Order and the Order's effect on consumers of Internet services and providers of the service, including a number of entities that had previously escaped FCC regulation.

At the recent Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) 80 Policy Forum meeting, one notable takeaway was its close focus on questions around the stability and security of the technical layer of the Internet: the growing risks which assail it, and potential ways to address these through governance.

At the recent Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) 80 Policy Forum meeting, one notable takeaway was its close focus on questions around the stability and security of the technical layer of the Internet: the growing risks which assail it, and potential ways to address these through governance.

Ajit Pai recently wrote an article in the National Review where he talks about how his decision as head of the FCC to repeal net neutrality was the right one. He goes on to claim that repealing net neutrality was the driver behind the current boom in building fiber and upgrading other broadband technologies. He contrasts the progress of broadband in the U.S. with Europe and says that the FCC's action is the primary reason we are seeing a fiber boom in the U.S.

Ajit Pai recently wrote an article in the National Review where he talks about how his decision as head of the FCC to repeal net neutrality was the right one. He goes on to claim that repealing net neutrality was the driver behind the current boom in building fiber and upgrading other broadband technologies. He contrasts the progress of broadband in the U.S. with Europe and says that the FCC's action is the primary reason we are seeing a fiber boom in the U.S.

On Friday, 23rd June, Caribbean telecommunications operators (telcos) held a meeting in Miami to fine tune their strategy to force Big Tech companies to contribute financially to regional telecoms network infrastructure. Hosted by the Caribbean Telecommunications Union (CTU), and taking a similar perspective to the "fair share" proposal currently being debated in the European Union, regional network operators are arguing that over-the-top (OTT) service providers are responsible for 67 percent of the total Internet traffic in the Caribbean, but make no contributions or investments toward local delivery networks.

On Friday, 23rd June, Caribbean telecommunications operators (telcos) held a meeting in Miami to fine tune their strategy to force Big Tech companies to contribute financially to regional telecoms network infrastructure. Hosted by the Caribbean Telecommunications Union (CTU), and taking a similar perspective to the "fair share" proposal currently being debated in the European Union, regional network operators are arguing that over-the-top (OTT) service providers are responsible for 67 percent of the total Internet traffic in the Caribbean, but make no contributions or investments toward local delivery networks.

Rudolph van der Berg presented on the latest updates from the ongoing tensions in the Internet industry between carriage infrastructure providers and content providers, with a European perspective. The carriage providers in the EU region are asserting that they're making major capital investments in augmenting the access network infrastructure to carry gigabit traffic volumes, which is largely streaming content, while at the same time the content providers were getting a free ride, or so goes the argument.

Rudolph van der Berg presented on the latest updates from the ongoing tensions in the Internet industry between carriage infrastructure providers and content providers, with a European perspective. The carriage providers in the EU region are asserting that they're making major capital investments in augmenting the access network infrastructure to carry gigabit traffic volumes, which is largely streaming content, while at the same time the content providers were getting a free ride, or so goes the argument.

There is an interesting recent discussion in Europe about net neutrality that has relevance to the U.S. broadband market. The European Commission that oversees telecom and broadband has started taking comments on a proposal to force content generators like Netflix to pay fees to ISPs for using the Internet. I've seen this same idea circulating here from time to time, and in fact, this was one of the issues that convinced the FCC first to implement net neutrality.

There is an interesting recent discussion in Europe about net neutrality that has relevance to the U.S. broadband market. The European Commission that oversees telecom and broadband has started taking comments on a proposal to force content generators like Netflix to pay fees to ISPs for using the Internet. I've seen this same idea circulating here from time to time, and in fact, this was one of the issues that convinced the FCC first to implement net neutrality.

The entire set of issues of network neutrality, interconnection and settlements, termination monopolies, cost allocation and infrastructure investment economics is back with us again. This time it's not under the banner of "Network Neutrality" but under a more directly confronting title of "Sender Pays." The principle is much the same: network providers want to charge both their customers and the content providers to carry content to users.

The entire set of issues of network neutrality, interconnection and settlements, termination monopolies, cost allocation and infrastructure investment economics is back with us again. This time it's not under the banner of "Network Neutrality" but under a more directly confronting title of "Sender Pays." The principle is much the same: network providers want to charge both their customers and the content providers to carry content to users.

Just as the last change in administration changed the course of the FCC, so will the swing back to a Democratic administration. If you've been reading me for a few years, you know I am a big believer in the regulatory pendulum. Inevitably, when a regulatory agency like the FCC swings too far in any direction, it's inevitable that it will eventually swing back the other way.

Just as the last change in administration changed the course of the FCC, so will the swing back to a Democratic administration. If you've been reading me for a few years, you know I am a big believer in the regulatory pendulum. Inevitably, when a regulatory agency like the FCC swings too far in any direction, it's inevitable that it will eventually swing back the other way.

EU Internet Advocates Push Back Against Telecom “Fair-Share” Fees

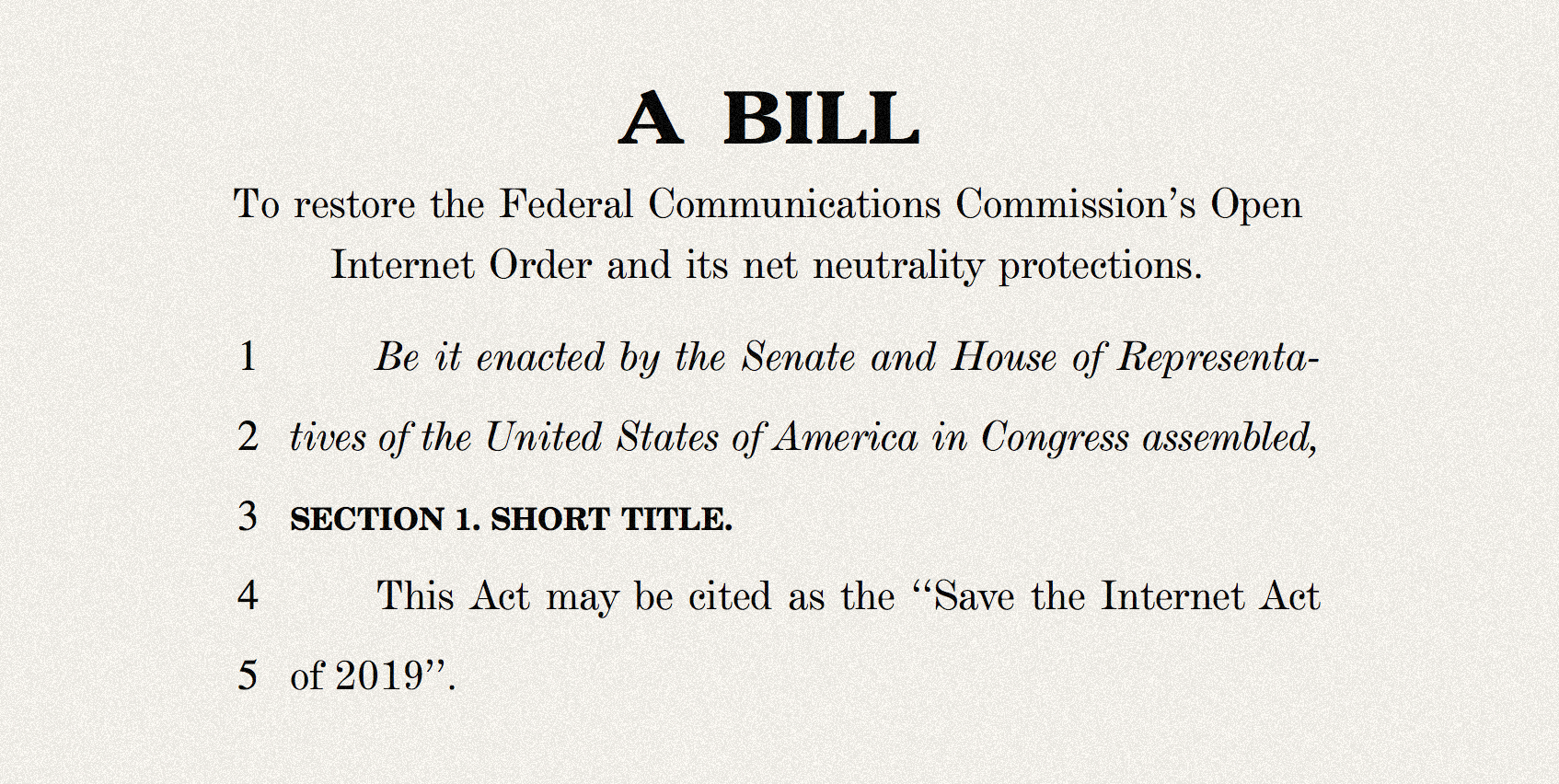

EU Internet Advocates Push Back Against Telecom “Fair-Share” Fees US House of Representatives Pass a Bill to Restore Net Neutrality Rules Repealed by Trump’s FCC

US House of Representatives Pass a Bill to Restore Net Neutrality Rules Repealed by Trump’s FCC