|

||

|

||

It’s no secret that I don’t very much like this whole private cloud or internal cloud concept (see here and here), on the basis that while advanced virtualisation technologies are valuable to businesses they are a severe short sell of what cloud computing is ultimately capable of. The electricity grid took over from the on-site generators very quickly and I expect cloud computing to do the same with respect to private servers, racks and datacenters. Provided that is the concept is not co-opted by threatened vendors pushing solutions that they claim are “just like cloud computing, only better”. The potential for cheap, commoditised computing resources far outweighs the benefits of in-house installations which carry few of the benefits that makes cloud computing so interesting (e.g. no capex, minimal support, access anywhere anytime, no peak load engineering, shared costs, etc.).

If you look at the overwhelming amount of coverage of cloud computing in the traditional sense versus the recent sporadic appearances of articles about private/internal clouds then the latter is what us Wikipedians call a fringe theory, and I’ve just treated it as such in the article (see below).

Interesting thing is this editor who appeared on the scene at the cloud computing article recently… Initially they sought to water down the references to open source software (which currently powers the overwhelming majority of cloud computing installations, e.g. Google, Salesforce and Amazon) but then they moved on to declaring that the very definition of cloud computing should be changed to accommodate private clouds (which is not going to happen so long as the overwhelming majority of reliable sources equate “cloud” to “Internet”).

The conflict of interest alarm bells were ringing already but it wasn’t until they pressed on with this change despite the absense of a consensus and protests from other editors that they were pushed to disclose affiliations. It was the redefining of “network computing” (an Oracle-ism and trademark from over a decade ago) to be a synonym for “cloud computing” using questionable sources that gave the game away and it wasn’t long before the editor revealed their identity as a Senior Software Architect at Oracle in the bay area.

That in itself isn’t a huge problem, after all conflict of interest is a behavioural guideline rather than a policy, but it is when there are associated policy violations like verifiability and neutral point of view as there were here. I’m still not sure what to make of Oracle’s new-found interest in cloud computing, especially after CEO Larry Ellison heavily criticised it in a speech last year, and it troubles me somewhat that these shenanigans are going on during business hours (I’d hate to think that they were assigned the task of “fixing” the article), but for now I’m assuming good faith and waiting to see what this editor comes up with next.

Anyway the result is that they’ve got their mention of private cloud/internal cloud, only it probably wasn’t exactly what they had in mind (that’s the law of unintended consequences for you). I’m sure this will be quite controversial with “I can’t believe it’s not cloud” vendors and their cronies but it’s supported by reliable sources and I believe an accurate representation of the consensus view. The term “private cloud”, so far as I am concerned, borders on deceptive advertising as it fails to deliver on the potential of cloud computing and those who attempt to use it to hang on the coat-tails of cloud computing should expect resistance.

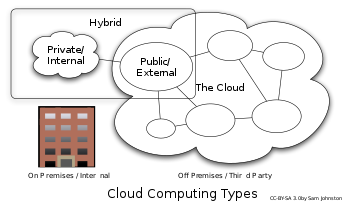

All is not lost though, as most of what people are calling “private clouds” have some “public cloud” aspect (even if just the future possibility to migrate) and can be classed as a “hybrid cloud” architecture. Indeed according to the likes of HP, Citrix and Nicholas Carr (and myself) most large enterprises will be looking to run a hybrid architecture for upto 5-10 years (though many early adopters have already taken the plunge). Yes it’s semantic but the important difference is that you’re not claiming to be a drop in replacement for cloud computing, rather a component of it. You can expect a lot less resistance from cloud computing partisans as a result.

Types [from Wikipedia: Cloud Computing]

Public Cloud

Public cloud or external cloud describes cloud computing in the traditional mainstream sense, whereby resources are dynamically provisioned on a fine-grained, self-service basis over the Internet, via web applications/web services, from an off-site third-party provider who shares resources and bills on a fine-grained utility computing basis.[63]

Public cloud or external cloud describes cloud computing in the traditional mainstream sense, whereby resources are dynamically provisioned on a fine-grained, self-service basis over the Internet, via web applications/web services, from an off-site third-party provider who shares resources and bills on a fine-grained utility computing basis.[63]

Hybrid cloud

A hybrid cloud environment consisting of multiple internal and/or external providers[64] “will be typical for most enterprises”.[65]

Private cloud

Private cloud and internal cloud are neologisms that some vendors have recently used to describe offerings that emulate cloud computing on private networks. These (typically virtualisation automation) products claim to “deliver some benefits of cloud computing without the pitfalls”, capitalising on data security, corporate governance, and reliability concerns. They have been criticised on the basis that users “still have to buy, build, and manage them” and as such do not benefit from lower up-front capital costs and less hands-on management[65], essentially “[lacking] the economic model that makes cloud computing such an intriguing concept”.[66][67]

While an analyst predicted in 2008 that private cloud networks would be the future of corporate IT,[68] there is some contention as to whether they are a reality even within the same firm.[69] Analysts also claim that within five years a “huge percentage” of small and medium enterprises will get most of their computing resources from external cloud computing providers as they “will not have economies of scale to make it worth staying in the IT business” or be able to afford private clouds.[70]

The term has also been used in the logical rather than physical sense, for example in reference to platform as a service offerings.[71]

As usual the diagram is available under a Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 3.0 license in PNG and SVG formats from the Wikimedia Commons (Cloud computing types.svg) so feel free to use it in your own documents, presentations, etc.

Sponsored byRadix

Sponsored byIPv4.Global

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byDNIB.com

Sponsored byWhoisXML API

Sponsored byCSC

What happens when the cloud vendor loses your data, or gets hacked? How do you explain to the auditors? Who’s going to send out the letters to the customers explaining their data has either been lost or worse, stolen?

This is why many corporations consider internalizing the “cloud”, which is just another reinvented word that’s in fashion these days. Two years ago they called it “grid”, the year before that it was “utility”, and before that it was ASP.

What happens when there’s a blackout and a company can’t make widgets any more? And in today’s lax legal environment, what’s the bigger risk? For most companies the key things are integrity and availability, not confidentiality. Regardless, cloud computing tends to be *more* secure than traditional systems rather than less.

Sam

Try telling your customers you violated their confidentiality and see how forgiving they are. With current disclosure laws, you can no longer ignore confidentiality.

Tell that to the guys who wrote the CISSP Exam Guide. That’s not to say I don’t care about security - I absolutely do (as a CISSP myself). Just that without notification laws et al businesses would have little motivation to care, which is in itself wrong (one could argue they should be liable for the associated damages but that’s another argument for another day).

For the most part cloud computing is more secure than traditional systems, and almost always “secure enough”.

Sam

And as I recall, a failure of any of those three is a major business disruption. A failure of any three will cost the company money. For some businesses, like that credit card processing company that handled all the VISA and Master Cards, a security breach put them out of business permanently.

Every business has different security requirements but when you look at your average business it is more important that they have access to their data when they need it and that the numbers are correct (e.g. an order to sell 10,000 shares is an order to sell 10,000 and not 1,000 or 100,000). I’ll concede that we haven’t yet achieved “dial tone availability” but it’s rapidly improving all the time and what we have today is “good enough” for most. By letting someone else take care of the details and sharing the costs with others businesses can get on with making widgets, which is why the early adopters of cloud computing are being well rewarded (at least the ones I’ve been dealing with).

I would suggest that companies with special security requirements (e.g. financial and a subset of government) should use providers with appropriate products and/or dedicated providers. As a business user I don’t want to have to pay for an extra “9” of availability and guard dogs in server cages for the sake of somebody else - those who need it can pay for it. Similarly, if I want to run a compute intensive job and the data is easily replaceable (e.g. by uploading again) then why should I pay for an expensive SAN to store it on when a local SATA disk would be fine? (This is something we don’t cater for well now - everyone has the same quality of service).

The market will cater for these needs and when cloud computing is commoditised they will be the only remaining differentiator.

Sam

There have been cases where a cloud vendor just flat out closes or changes something and declares that they can’t get you your data back. One vendor outsourced to a second vendor and the second vendor changed something and refused to convert customer data. The two vendors pointed fingers at each other and the customers got screwed.

There are many problems with the cloud “availability” argument. For one thing, you’re relying on an Internet connection that is always available so no matter how good the cloud vendor is, if the connectivity is broken, it’s broken as far as the user is concerned. Secondly, “availability” to consumers also means speed. Data in the cloud is extremely slow compared to a local server farm. We’re talking speed differences of possibly 100 to 1. Thirdly, even the best cloud platforms like Gmail and Salesforce have had some serious availability problems in the past and not just the connectivity issues.

The security problem with public clouds is a particularly difficult one. In this case, you’re fundamentally relying on a different company to handle your data. When I worked for CNET, one of the companies they outsourced one of their applications to suffered a breach and every current and past employee was affected. I got one of those letters telling me my personal data was compromised.

The bottom line with public clouds is that they are merely one alternative for some businesses. It is not THE solution for everyone. Nothing is the solution for everyone. There are people who are paid to say their solution is the best thing since sliced bread, but that has little resemblance to reality. Public clouds make sense to smaller businesses who do not have the scale to internalize IT. It makes little sense when a business already have internal or contracted IT staff.

Another assessment of cloud computing types is present at theCloudTutorial.