|

||

|

||

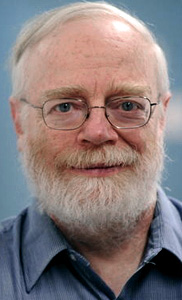

Fred Brooks passed away on November 17. He was a giant in computer science and a tremendous inspiration to many of us.

Brooks is famous for many things. Many people know him best as the author of The Mythical Man-Month, his musings on software engineering and why it’s so very hard. Some of his prescriptions seem quaint today—no one these days would print out documentation on microfiche every night to distribute to developers—but his observations about the problems of development remain spot-on. But he did so much more.

He started his career at IBM. One of his early assignments was to NSA; among other things, when back at IBM, he worked on the design of Harvest, the character-processing auxiliary processor to the IBM 7030. (When I took computer architecture from him, I learned to recognize some characteristics that made for a good cryptanalytic machine. He, of course, was working back in character cipher days, but it’s remarkable how many of those same characteristics are useful for attacking modern ciphers.)

He was also a lead on a failed project, the IBM 8000 series. He tried to resign from IBM after it failed; Watson replied, “I just spent a billion dollars educating you; I’m not letting you go now!”

He then headed the project that designed and built the IBM S/360 series of mainframes. It was an audacious concept for the time—five different models with vastly different prices and performance characteristics, but all sharing (essentially) the same instruction set. Furthermore, that instruction set was defined by the architecture, not by some accident of wiring. (Fun fact: the IBM 7094 (I think it was the 7094 and not the 7090) had a user-discovered “Store Zero” instruction. Some customers poked around and found it, and it worked. The engineers checked the wiring diagram and confirmed that it should, so IBM added it to the manual.) There were a fair number of interesting aspects to the architecture of the S/360, but Brooks felt that one of the most important contributions was the 8-bit byte (and hence the 32-bit word).

He went on to manage the team that developed OS/360. He (and Watson) regarded that as a failure; they both wondered why, since he had managed both. That’s what led him to write The Mythical Man-Month.

He left IBM because he felt that he was Called to start a CS department. This was an old desire of his; he always knew that he was going to teach someday. (Brooks was devoutly religious. Since I don’t share his beliefs, I can’t represent them properly and hence will say nothing more about them. I will note that in my experience, at least, he respected other people’s sincere beliefs, even if he disagreed.)

I started grad school at Chapel Hill a few years later. Even though he was the department chair, with many demands on his time—he had a row of switch-controlled clocks in his office so that he could track how much time he spent on teaching, research, administration, etc.—he taught a lot. I took four courses from him: software engineering (the manuscript for The Mythical Man-Month was our text!), computer architecture, seminar on professional practice, and seminar on teaching. I still rely on much of what I learned from him many years ago.

Late one spring, he asked me what my summer plans were. “Well, Dr. Brooks, I’d like to teach.” (I’d never taught before but knew that I wanted to, and in that department at that time, Ph.D. students had to teach a semester of introductory programming with full classroom control. I ended up teaching it four times because I really liked teaching.)

Brooks demurred: “Prof. X’s project is late and has deliverables due at the end of the summer; I need you to work on it.”

“Dr. Brooks, you want to add manpower to a late project?” (If you’ve read The Mythical Man-Month, you know the reference—and if you haven’t read it yet, you should.)

He laughed and told me that this was a special case and that I should do it, and in the fall, I could have whatever assistantship I wanted. And he was 100% correct: it was a special case where his adage didn’t apply.

Brooks was dedicated to education and students. When it came to faculty hiring and promotion, he always sought graduate student input in an organized setting. He called those meetings SPQR, where the faculty was the Senate. In one case that I can think of, I suspect that student input seriously swayed and possibly changed the outcome.

He had great confidence in me, even at low points for me, and probably saved my career. At one in my odd grad school sojourn, I needed to take a year off. I had a faculty job offer from another college, but Brooks suspected, most likely correctly, that if I left, I’d never come back and finish my Ph.D. He arranged for me to be hired in my own department for a year—I went from Ph.D. student to faculty member and back to student again. This was head-spinning, and I didn’t adapt well at first to my faculty status, especially in the way that I dressed. Brooks gently commented to me that it was obvious that I still thought of myself as a student. He was right, of course, so I upgraded my wardrobe and even wore a tie on days that I was teaching. (I continued to dress better on class days until the pandemic started. Maybe I’ll resume that practice some day…)

At Chapel Hill, he switched his attention to computer graphics and protein modeling. He’d acquired a surplus remote manipulator arm; the idea was that people could use it to “grab” atoms and move them, and feel the force feedback from the varying charge fields. From there, it was a fairly natural transition to some of the early work in VR.

Two more anecdotes, and then I’ll close. Shortly after the department had gotten its first VAX computers, a professor who didn’t understand the difference between real memory and virtual memory fired up about ten copies of a large program. The machine was thrashing so badly that no one could get anything done, including, of course, that professor. I was no longer an official sysadmin, but I still had the root password. I sent a STOP signal to all but one copy of the program, then very nervously sent an email to that professor and Brooks. Brooks’ reply nicely illustrates his management philosophy: “if someone is entrusted with the root password, they have not just the right but the responsibility to use it when necessary.”

My last major interaction with Brooks while I was a student was when I went to him to discuss two job offers from IBM Research and Bell Labs (not Bell Labs Research; that came a few years later). He wouldn’t tell me which to pick; that wasn’t his style, though he hinted that Bell Labs might be better. But his advice is one I often repeat to my students: take a sheet of paper, divide it into two columns, and, as objectively as you can, list the pluses and minuses of each place. Then sleep on it, and in the morning, go with your gut feeling.

Frederick P. Brooks, Jr.: May his memory be for a blessing.

Sponsored byCSC

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byIPv4.Global

Sponsored byWhoisXML API

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byRadix

Sponsored byDNIB.com