|

||

|

||

From the creation of DNSAI Compass (“Compass”), we knew that measuring DNS Abuse1 would be difficult and that it would be beneficial to anticipate the challenges we would encounter. With more than a year of published reports, we are sharing insights into one of the obstacles we have faced.

One of our core principles is transparency and we’ve worked hard to provide this with our methodology. Now we’d like to share more information on some underlying data and a challenge with edge cases: domains that appear suspicious, but after investigation do not conclusively reach the threshold for mitigation action.

This post was written in collaboration with Identity Digital and KOR Labs. This ‘.productions’ data was published with permission from Identity Digital. We thank Identity Digital for being cooperative and transparent in letting us discuss this scenario.

This blog covers an interesting case of suspected abuse in a gTLD registry between February and April 2023. It is a good example of an edge case, where the decision on whether or not to mitigate was not clear cut, and different levels of evidence were available at different times. While there was some evidence of DNS Abuse, it was not sufficient at the time of registry investigation, and reasonable minds could come to different conclusions based on the evidence that was collected.

This case was also further complicated due to the source feed incorrectly labeling the suspected abuse as ‘phishing’ instead of ‘malware’ which impacted the ability of the registry to collect evidence. Correct classification of the type of abuse can have a significant impact on the speed of the investigation and even impact the results.

This case also appeared to be linked to a previous attack with similar hallmarks in a different Top Level Domain (TLD). There was a similarity in the alphanumeric pattern of the domain registrations, but other evidence was not visible when Identity Digital investigated. The suspected abuse appears to have involved thousands of unique domain names. It therefore raises a question of how evidence could or should be extrapolated between domains that appear to be registered for related (potentially malicious) reasons with different registrants in different TLDs.

This case provides a real world example of how an abuse manager often needs to make a difficult decision, with limited evidence, that could impact a large number of domains. It also demonstrates some of the complexity involved in measuring and mitigating DNS Abuse.

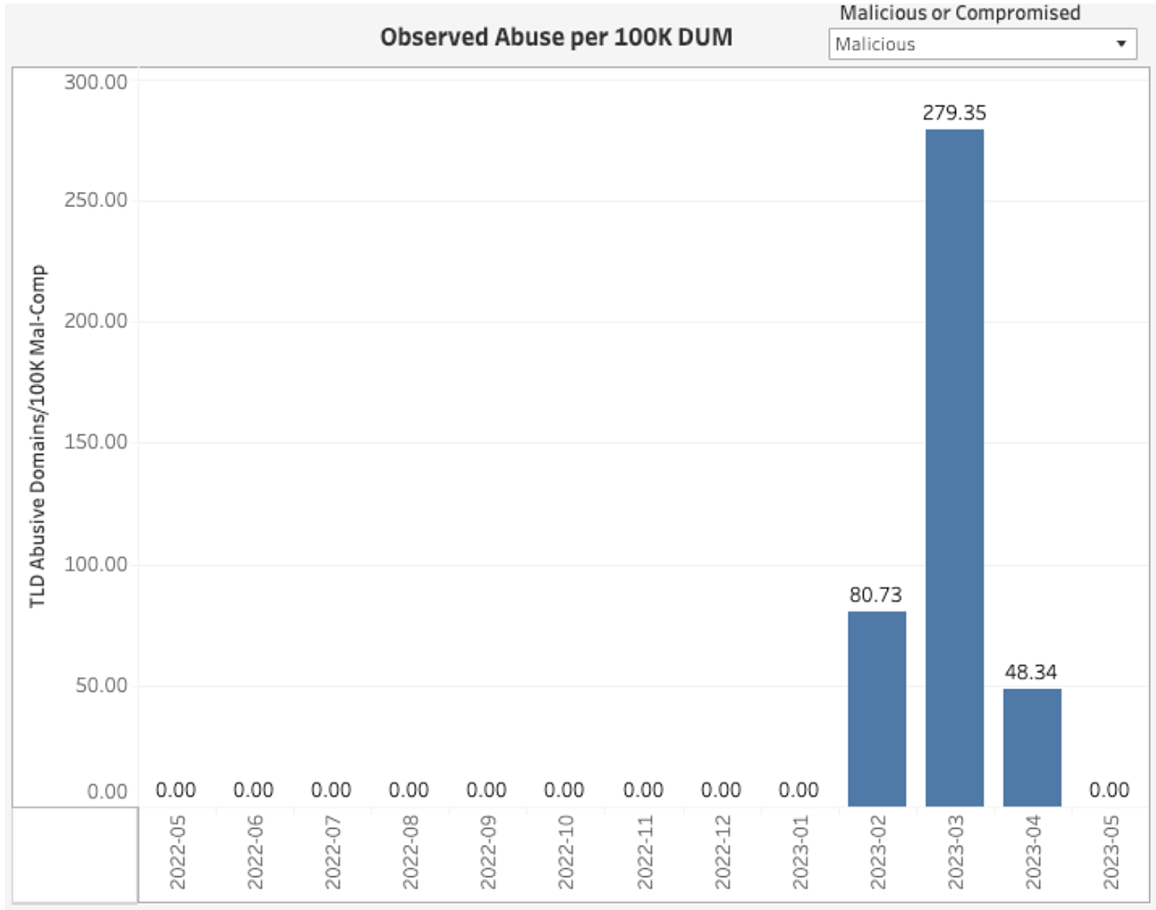

The ‘.productions’ TLD is managed by Identity Digital and has previously had a spotless record in Compass with zero domains identified as phishing or malware for most months on record. However, data in March 2023 showed an unusually high number of malicious registrations with 63 unique domains. These were identified as ‘phishing’ by a source feed and categorized as ‘malicious’ (as opposed to ‘compromised’) by the KOR Labs methodology used in Compass and screen shots were recorded by KOR Labs at the time.

The registry operator, Identity Digital (ID), proactively engages in practices to manage abuse. They are one of the few registries that publish an Anti-Abuse report—a great effort to create transparency on abuse and mitigation. As a proactive registry, they have policies and systems in place to alert them to potential abuse and take action when appropriate. ID reviews a number of abuse feeds and other data sources, using both trained staff and software systems to determine whether there is sufficient evidence for the registry to mitigate the abuse.

ID receives notifications through almost all of the source feeds used in Compass, so in this case, ID was notified of a potential issue in .productions. These notifications were labeled as ‘phishing.’ At the point of investigation, ID could not find any concrete evidence of phishing or malware.

They did find a pattern to these domain names similar to other malware campaigns they have seen in the past, in other TLDs they manage. That pattern was a similar style of domain name in a clear alphanumeric pattern. In ID’s prior experience with this pattern, they were able to find hosted malware, specifically a malicious APK (Android Packaging Kit) download, which is an Android Package file extension typically used for installing applications outside of the Android application store.

While these patterns indicated that the domains could be used maliciously in the future, or may have been used maliciously in the past, there was no clear evidence of hosted malware at the point in time that ID investigated the names in .productions. The registry therefore concluded that the evidence at that time was insufficient to justify mitigating action, though it was keeping those domains under closer watch.

It is the role of each registry or registrar operator to responsibly and reasonably determine their threshold for mitigation action, and the associated evidence they require. Mitigation does not come without risks—legal, reputational, collateral damage—and therefore should be carefully considered in each circumstance

As the more direct owner of the customer relationship, the registrar often has more information available to assess abuse reports. In the case discussed above, ID had one registrar who suspended a large proportion of domain names, and others that found there was insufficient evidence to suspend any domain names. Although this may have also been a result of the timing of their assessment of the evidence.

As this case demonstrates, assessing and acting on abuse is complex. Many cases are not straightforward and one potentially malicious campaign can involve hundreds or thousands of domain names.

Were these domains abusive? Not conclusively at least from the registry perspective—at the time that they investigated.

This example highlights a few important points. First, timing is essential and challenging. Depending on when the operator is notified, it may be too early or too late to find the requisite evidence to take action.

Second, labeling is important. These domains were reported in source feed as ‘phishing’ but they were actually more likely to have been associated with ‘malware’. Classification can have a significant impact on the speed of the investigation and even impact the results. Registries and registrars often refine their investigation process around the attributes of different types of abuse, which could mean an incorrect label results in no evidence being identified. This is especially relevant if the operator uses an automatic parsing system. These can be useful to manage the high number of abuse reports received on a daily basis and can form part of an escalation pathway.

Third, how much should a registry or registrar extrapolate from similar patterns in other TLDs if they have the data available. The screenshots collected by KOR Labs at the time of blocklisting did have similarities with the screenshots of the previous campaigns in different TLDs, but they were not present at the time ID investigated the campaign in .productions.

Does this mean measurement is futile? We don’t think so. A challenging edge case is not evidence to give up on measurement, but it is a reminder of the difficulties and nuances involved. It’s a great example of why our measurement project needs to expand to share more detailed information with registries and registrars, and to reach a point where we are improving the quality of the underlying data with a feedback mechanism. Both are elements we have been exploring with registrars and registries for over a year.

It’s also a good reminder that there is no perfect source list of DNS Abuse. False positives are a real challenge and we must keep this in mind as we interpret and present data.

For now, it’s a good test case for our existing metrics and presentation of data, which were chosen with the hope that they would minimize the impact of false positives and one-off targeted attacks impacting registrars and TLDs that have an otherwise clean record when it comes to abuse.

In our June 2023 Compass report, we saw .productions temporarily rise into ‘Table 9: gTLDs in descending order of highest observed maliciously registered domains per 100,000 DUM.’ However, the ‘.productions’ data was redacted as they never met our consistency requirement: ‘If a TLD does not appear in the list ... for 4 or more of the last 6 months, its data has been redacted’. We are grateful to ID for allowing us to publish this blog with identification of the TLD to shine a spotlight on the challenges of measuring DNS Abuse.

Redaction seems to be the right conclusion in this case, given the inconclusive evidence and the one-off nature of this attack. May 2023 saw ‘.productions’ return to its usual state of zero observed malicious abuse per month: see Figure 1.

This case highlights two interesting conversations for the industry. First, is there any consensus on what a minimum standard of evidence should be for mitigation at the DNS level? This will no doubt be a topic of consideration for some time following the anticipated gTLD contract amendments and subsequent expected policy development processes.

Second, is there anything a registry or registrar should do with suspicious domain names? Generally, the option for registries and registrars is “all or nothing,” but we may seek to explore whether any other measures could be feasible in the case of a suspicious domain name that does not cross the mitigation threshold.

We look forward to improving Compass in the future and continuing to work with the community on these issues. Please contact us with comments or questions.

Sponsored byRadix

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byIPv4.Global

Sponsored byCSC

Sponsored byDNIB.com

Sponsored byWhoisXML API