|

||

|

||

Section 706 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 orders the FCC to “encourage the deployment on a reasonable and timely basis of advanced telecommunications capability to all Americans.” On October 25, The FCC issued a notice of inquiry (NOI) into how well we are doing and invited comments.

The NOI points out that COVID and the concomitant increase in the use of interactive applications has “made it clear that broadband is no longer a luxury but a necessity that will only become more important with time” and proposes “an increase from the existing fixed broadband speed benchmark of 25 Mbps download and 3 Mbps upload (25/3 Mbps) to 100/20 Mbps.” They also seek comment on a long-term speed goal of 1,000/500 Mbps.

The focus is clearly on speed. They mention latency on page 12 and jitter and packet loss on page 15, but the FCC made no metrics recommendations on those metrics and requested comments.

Dave Taht, Chief Science Officer of LibreQOS and an embedded Linux developer and consultant since 1998, drafted a comment arguing that the FCC should “balance its near-term efforts on achieving Internet resilience and minimizing latency, instead of only increasing speed.” Taht invited experts to suggest edits to and sign his draft, and the submitted comment has 63 signatures, many of which would be familiar to CircleID readers.

Taht says, “Calls for further bandwidth increases are analogous to calling for cars to have top speeds of 100, 500, or 1000 miles per hour,” and the “only way to improve responsiveness is to robustly and reliably reduce the latency, and especially the ‘latency under load.’” He points out that low latency, not speed, is critical for today’s interactive applications, and high latency reduces aggregate network efficiency and increases variability in the user experience.

Much Internet latency is caused by bufferbloat—packets working their way through queues that build up in routers and other network equipment. Taht has spent years developing tools to measure latency and reduce bufferbloat, and he documents his work and that of others in his 27-page NOI comment.

That depends on the applications you use, which is a moving target. My first home Internet terminal was a 10-character per-second (CPS) ASR-33 Teletype with an acoustic coupler. I used it for email, FTP, Telnet, and network news, and I was able to collaborate with distant colleagues. I loved it, and 100 CPS would not have made a big difference because 10 CPS was about as fast as I could read and faster than I could type. My first connected computer used a 300-bps modem, and modem speeds increased to 56 Kbps driven by applications like Web and voice over IP.

Today, Poa Internet in Kenya offers uncapped 4 Mbps service which is sufficient for downloading software, articles, books, movies, etc., shopping, making voice-over-IP calls, listening to podcasts, reading newspapers, etc., and, importantly, creating content and inventing and developing applications and services that are relevant to Africa.

Streaming video is the most speed-intensive application I use today, and Netflix recommends 15 Mbps for viewing UHD 4k movies. Poa Internet customers might be able to view 720p video.

| Video quality | Resolution | Recommended speed |

|---|---|---|

| High definition (HD) | 720p | 3 Mbps or higher |

| Full high definition (FHD) | 1080p | 5 Mbps or higher |

| Ultra high definition (UHD) | 4K | 15 Mbps or higher |

Spectrum, my ISP today, offers three plans —up to 300, 500, and 1,000 Mb/s. I have a 300 Mbps cable connection, which is more than I need. M-Lab’s Internet performance test service, which measures speed and latency unloaded and while simulating background activity, reported that my latency increased from 16 to 53 ms when downloading was active and 41 ms when uploading was active. Speeds were 355.3 Mbps download and 11.2 Mbps upload. Considering Netflix’s recommendation, it is unsurprising that streaming two movies on my home WiFi network while running the M-Lab test did not make much difference.

As long as I only watch one movie at a time, I suspect I would not notice much difference if Spectrum only provided me with the current FCC benchmark of 25/3 Mbps. This raises the question of opportunity cost. How much capital and operating cost could Spectrum have saved if they had only provisioned, say, a choice between 25/3 and 50/6 Mbps? Would the savings be sufficient to fill in white spaces in their national broadband map?

Spectrum dismisses latency, writing:

Latency is typically measured in milliseconds and generally has no significant impact on typical everyday internet usage. As latency varies based on any number of factors, most importantly the distance between a customer’s internet-connected device and the ultimate internet destination (as well as the number, variety, and quality of networks your packets cross), it is not possible to provide customers with a single figure that will define latency as part of a user experience.

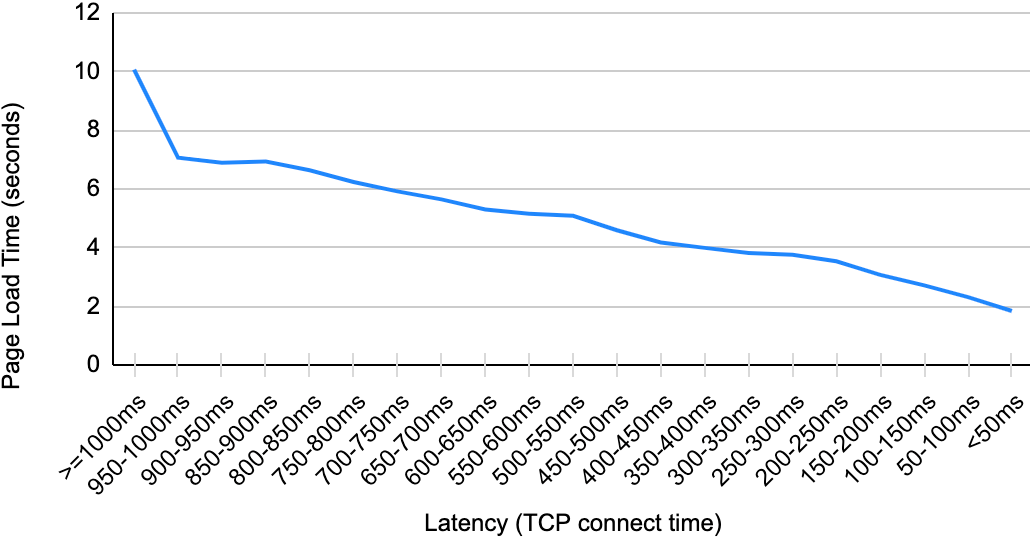

If we could come up with a “single figure” to define and measure latency, ISPs would have an incentive to improve it, and the FCC could adopt benchmarks. While a single figure may be impossible, could tests isolate the latency in an ISP network and the customer premises equipment (CPE) they supply? Could we use imperfect surrogates for latency, like page-load times? Could we benchmark components like the CPE an ISP provides?

While the FCC and ISP marketing are focused on speed today, attention to latency and its measurement is growing within the technical community. To learn more and get involved, check Dave’s Bufferbloat.net site and LibreQOS and watch Dave’s talk here. You can also give the FCC feedback by commenting on Proceeding 22-270 on the FCC Express Comments Page.

Update Jan 18, 2024:

Elon Musk summarized SpaceX’s 2023 accomplishments in a recent talk at Starbase in Texas, He covered many topics including Starlink. He stated that their biggest single technical goal for the year was to get mean latency under 20 ms. (He estimated that 10 ms was the theoretical minimum given the speed of light). Doing so will require a combination of steps including launching satellites with inter-satellite laser links, adding ground stations, and heeding the advice Dave Taht has been offering for years.

Update Jul 15, 2024:

SpaceX Starlink has begun delivering on Elon Musk’s commitment to reduce latency, and they are letting users know by including latency values and distribution in the Starlink app. (The 100 ms latency spike at the end of the distribution must reflect handoffs between satellites).

All ISPs should report and advertise latency as well as throughput, which is less important than latency in many applications.

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byRadix

Sponsored byWhoisXML API

Sponsored byIPv4.Global

Sponsored byDNIB.com

Sponsored byCSC

Sponsored byVerisign

Larry, as usual, is correct and there are numerous dimensions to the quality of service. In the BEAD NOFO there is specific language on latency and also QOS relative to delivered speeds.

The latency issue is highly complex and any single measurement will not completely test the full user experience, especially when we are looking at complex web pages where DNS hits alone can cause poor user experience.

But speed does matter, and looking at download as the primary demand may not suffice for future applications or real world environments where multiple concurrent users need adequate QOS. We need to get good enough connectivity to all users and more important not do it in a way that perpetuates the lack of digital equity that currently exists.