|

||

|

||

In part three of this series of posts looking at emerging internet content relating to coronavirus, we turn our attention to mobile apps—another digital content channel that can be used by criminals to take advantage of people’s fears about the health emergency for their own gain.

One of the most common attack vectors we have found in our analysis is the use of apps purporting to track global progression of COVID-19, or provide other information, but which instead incorporate malicious content. In mid-March, CovidLock ransomware was reported. It was distributed through a coronavirus-specific domain name, and threatened to leak users’ social-media information and delete smartphone file storage unless a Bitcoin ransom was paid1, 2. Prior to this, reports emerged of a number of online resources masquerading as legitimate coronavirus trackers, but which actually distribute malware. In one example, a website directed users to open an applet that could infect their device with AZORult, a piece of malware used to steal login credentials and banking information3. An Android app named Corona Live 1.1 also purports to be an official coronavirus tracker that incorporates information from the (legitimate) Johns Hopkins tracker, but actually features malware, allowing attackers to record the victim’s location, and access photos, videos, and the camera on their device4.

In general, mobile apps can be downloaded from two main sources. The first of these is the group of main app stores such as Google Play™, iTunes, Amazon® Appstore, and Microsoft® Store, but there are also a huge number of stand-alone app download sites. These are often called APK download sites, in reference to Android package file-format used for the distribution of Android mobile apps. Content on the main app stores tends to undergo a much more rigorous verification process for quality and legitimacy, while the APK sites can be less trustworthy, and may feature app versions that are non-legitimate, associated with malicious content, or are out of date (therefore lacking the most recent security patches). This said, even the main app stores are not immune to dangerous content. It was reported that the Iranian government distributed a piece of spyware in the guise of an Android app purporting to monitor for COVID-19 symptoms; this app was initially made available on the Google Play store, before being removed due to a violation of the marketplace’s terms and conditions5, 6.

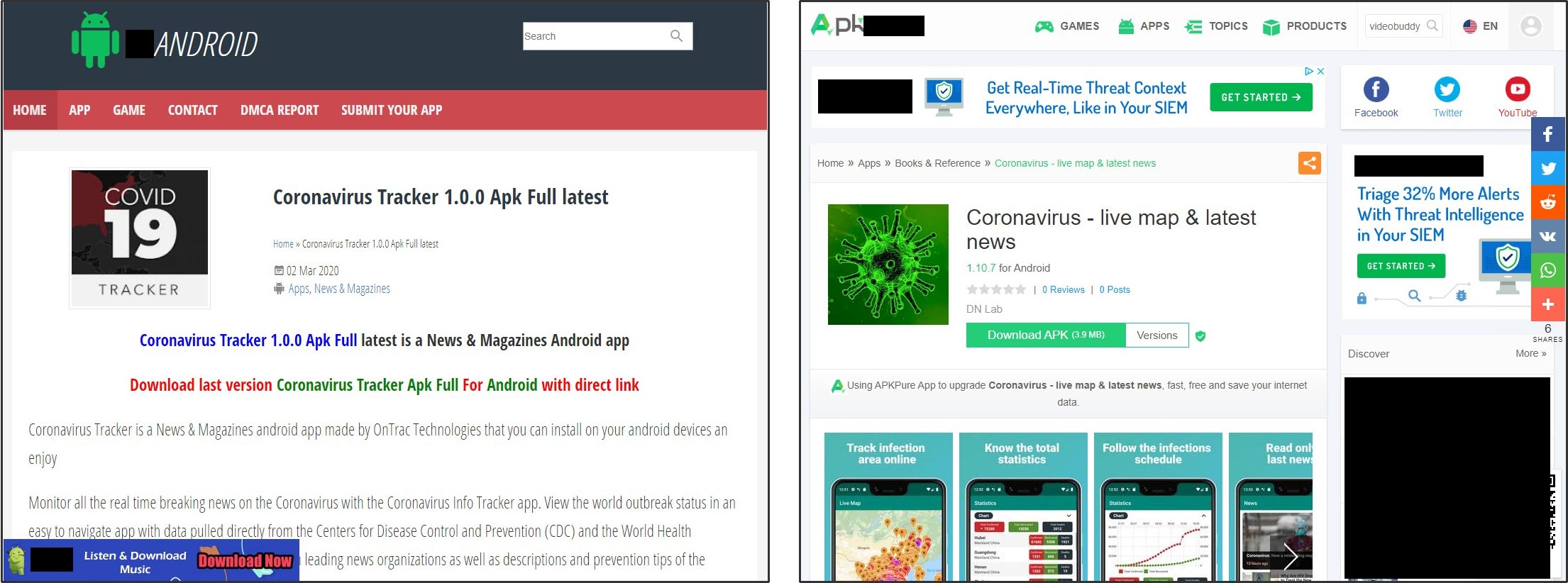

Currently, a relatively small number of coronavirus-related apps are on offer across the main app marketplaces, comprising a mixture of information apps, health checkers, and infection trackers. Across the ecosystem of APK sites, however, a much larger range of mostly tracker apps is on offer. A simple search engine look-up for “coronavirus” plus “APK download” returns a significant number of listings. While some of the apps thus identified may be legitimate, they raise the potential for risk, for any of the reasons outlined above.

Mobile app monitoring across all marketplaces and APK sites should form part of any comprehensive brand protection service. A monitoring system can search for brand terms in the name or description of mobile apps, or in the developer or seller names. Third-party apps incorporating branded content are of concern if any of the following apply:

For infringing apps, it’s often possible to take enforcement action to have the listing removed. Enforcement usually involves completing a web form or submitting an email, detailing the infringement criteria the app meets. As for many areas of brand protection, the likelihood of success is dependent on the level of IP protection held by the brand owner, and specifically on whether trademarks are held in the appropriate classes.

Sponsored byWhoisXML API

Sponsored byDNIB.com

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byIPv4.Global

Sponsored byCSC

Sponsored byRadix