|

||

|

||

Rights and Duties, Digital Citizenship, Residency, Political Crime, Asylum, Digital Slavery/Servitude — Co-authored by Prof. Sam Lanfranco and Klaus Stoll.

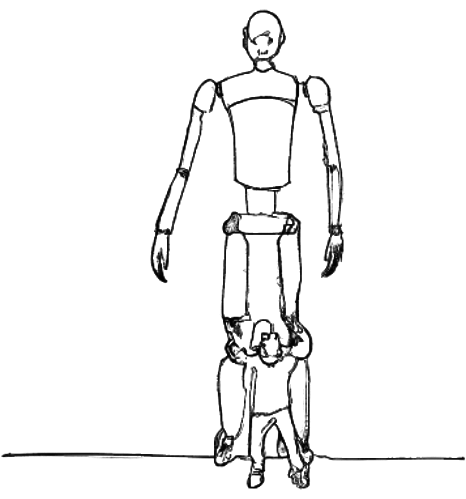

Nationality defines a person’s legal relationship to the state, giving the state jurisdiction over the person. In turn, the person enjoys rights and duties protection from the state. Today, the digital domain bestows on each of us a dual but inseparable physical and digital citizenship. Even if we don’t know about the digital domain or are unable or have decided not to use any of the digital technologies, we are still digital citizens with rights (and corresponding duties). Our lives, one way or another, are affected by that citizenship. Building from the UDHR, digital citizenship comes with the same fundamental rights that every physical and digital person should enjoy. The design of systems of digital governance to enshrine this is the pressing task at hand.

The global and virtual character of the digital domain makes it a space where the will of its residents is the single source of its sovereignty. Sovereignty in the digital domain means sovereignty based on the will of the people that occupy it. At one crucial level, it is global and not territory or slice of the globe.

Governments will have to learn and consider that national citizens are also citizens of a global cyberspace that transcends the sovereign bounds of the nation-state. That is not a new situation for governance. Much of the Digital domain is like the earth’s oceans or atmosphere. It transcends national boundaries. While there will be national digital governance, there will have to be global agreement on the governance of the digital domain. This will most likely be resolved much in the way we have multilateral agreements dealing with oceans and the atmosphere. The role of the state differs a bit in the digital domain. The issue is not only about the shared use of a common resource, but that states will have to enter a working relationship not just with other states and their citizens but a new global and sovereign “we the people” in the form of the global digital citizenship.

At the level of the global digital domain, the issue of global digital citizenship is complex. Everyone is a de facto resident and global citizen of the digital domain, but the rights and obligations of global digital citizenship and the key issues of how they should be defined and who should be involved in formulating them are still unresolved.

To delineate between national digital citizenship and citizenship within the cyberspaces of the Digital domain, we use the term digital citizenship for the former and global digital citizenship for the latter. In both cases, effective democracy calls for engaged citizenship, engaged digital citizenship, and engaged global digital citizenship. Here our focus is on stakeholders engaged in global digital citizenship.

It is essential for the governance of cyberspace that policymaking and enforcement tools are in place that ensure global digital citizens are empowered in the policymaking processes, are never deprived of their full rights (and duties) citizenship and enjoy a safe and secure residence in the cyberspaces of the Internet. The UDHR not only defines the values and key principles that should be enshrined in a declaration of digital rights, or more properly, the rights of global digital citizenship, but it also describes the necessary instruments of governance. (see below” The instruments of Governance”)

Establishing the rights and duties of digital citizenship will likely be a two-stage process. The first stage will involve identifying and subscribing to a set of basic principles in a digital bill of rights. The second stage will be the process of legislative and behavioral changes over time.

It is likely that global digital citizenship will develop in two directions, upward from the refinement of national digital citizenship and downward from principles and ideas, starting with the notion of a global digital citizenship that exists in addition to and partially apart from one’s national digital citizenship.

Our digital residence in the cyberspaces of the global Digital domain stands in marked contrast to our digital residence where we reside. Governments have sovereignty and authority over domestic cyberspace. Persons and entities have a state-defined digital citizenship and residency. They also now have a nation-like digital residence in the global digital domain.

Article 13: (1) gives everyone the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of a state. Residence and citizenship are not necessarily the same, so Article 13 does not address rights and duties regarding citizenship. Residency in cyberspace operates both within the nation-state and globally outside the nation-state. Ideally, there should be only one set of cyberstate policies and regulations, one digital citizenship for all. However, nation-states can and do distinguish between residence and citizenship. They may have different policies for each, policies that also differ from those of other nation-states. At the global level, that is not the case. In global cyberspace, everyone is a global resident and, by extension, a global citizen. There is no way to differentiate between the two. There is no way to acknowledge global residency but deny global citizenship.

The power and legitimacy of cyber governance stem from the recognition of a state’s sovereignty and its right to govern domestic cyberspace. Within one’s country citizenship, national digital citizenship comes under the governance of that domestic cyberspace. At the same time, persons and entities have a global residence in cyberspace and may have local residences in other countries. This raises the issue of digital migration and one’s ability to change digital residence across states and governments at will. At the same time, this leaves open our understanding of what digital citizenship means at the global level. ICANN, responsible for the security and stability of the global Internet, has a motto that states: “One World, One Internet.” What that means in terms of global digital citizenship, domestic digital citizenship, and cyberstate governance is yet to be worked out. Ideally, this will be determined, consistent with and with help from, the principles in the UDHR.

One important complication is that in digital space, one also has a global presence and residency. This calls for attention to developing multilateral (global) policies that enshrine one’s rights and responsibilities as a global digital citizen. One is directed to how we have addressed the laws of the sea and space.

Article 15: (2) of the UDHR states that: “No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality.” This confronts us with an interesting conundrum in global cyberspace. While one’s national and global digital residency can be protected or abridged by the actions of one’s nation-state, and by multilateral agreements, what might it mean to change one’s digital nationality? As well, given the fluid definition of nationality, one may well possess multiple digital nationalities. If states arbitrarily abridge digital citizenship rights in cyberspace, what are the citizen’s options? One can, of course, exercise engaged participation to try to enshrine and protect digital rights. One can resist when confronted with tactics contrary to the universal principles enshrined in the UDHR, or enshrined in subsequent global digital citizenship covenants.

Does one have a right, or a possibility, to secede? The answer is both a yes and a no. One can secede from a state’s jurisdiction by emigration, but one cannot secede from the global cyberspaces of the Digital domain any more than one can secede from earth’s gravity. The mere fact of existing now makes one a resident of global cyberspace. One is likely to have residency even prior to birth.

What this means is one’s presence is preordained, that one has a duty and an obligation to willfully become an engaged digital citizen in the cyberspaces of the Digital domain from the moment one is capable of measured and deliberate action. This does not mean a childhood engagement in the governance processes, but it does mean a progressive learning and understanding of integrity-based engagement in policy and behavioral norms that make one a responsible, engaged digital citizen of the national and global digital domains.

Political crimes in the context of the UDHR are considered an abuse of human rights. A political crime or acts contrary to the purposes and principles of the UN. States may define political crimes as any behavior perceived as a threat, real or imagined, to the state’s survival, including both violent and non-violent oppositional crimes. Such criminalization may curtail a range of human rights, civil rights, and freedoms. Under such regimes, conduct that would not normally be considered criminal per se is criminalized at the convenience of the group holding power.

Digital citizens experiencing digital exploitation and manipulation have the right to engage in peaceful acts of civil disobedience. The right of assembly to protest peacefully has long been accepted as essential. In the context of the UN, peaceful is defined as the absence of war based on international law. Peaceful means not just the absence of physical violence. Many forms of violence exist that are not physical but mental and psychological, and they may target the individual, the group, or the social fabric of society.

Asylum is the mechanism that protects human rights against arbitrary state power. For digital asylum to have meaning, it might have to be accompanied by physical migration.

Digital citizens experiencing persistent digital exploitation, manipulation and persecution have the right to asylum. Everyone has the right to seek and enjoy in other countries asylum from digital persecution. Asylum is the mechanism that protects human rights against arbitrary state power, be it driven by political, economic, religious or other forces.

Extending the notion of asylum to the protection of one’s digital residency and citizenship is one of the challenges on the global Internet policy and governance agenda. In the digital domain, there is nowhere to go, nowhere to hide. If one has been persecuted or prevented access within one’s digital residency, digital migration still leaves the literal person open to persecution. For digital asylum to have meaning, it has to be accompanied by physical migration and the granting of asylum.

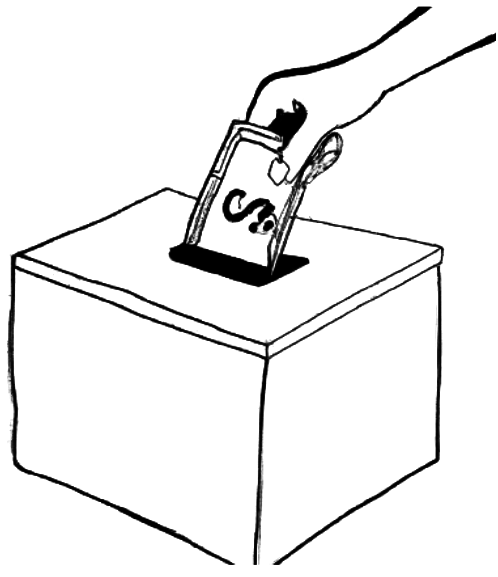

A state of digital servitude (near-slavery) exists when a person, in order to communicate, interact, or conduct business in the digital domain, is forced to accept conditions that are contrary to its human rights and interest. If a person does not have the freedom and ability to control its personal data, it lives in a state of digital servitude.

Digital slavery occurs when someone takes ownership of another person’s digital data with the intention to manipulate and exploit its behavior of that person on and offline. Practices that seek access to and use personal digital data (such as in user agreements) require explicit and clear terms of agreement if they are not to become instruments of digital slave trade, resulting in literal or digital slavery or servitude. A digital slave trade occurs when the personal data of digital citizens is traded between entities without the person’s consent.

The digital domain encompasses the different spaces and spheres we use to relate and interact with the people and things that surround us using digital technologies. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, UDHR, as the globally accepted standard, should serve us as the guiding light when it comes to striking the delicate balance between our rights and responsibilities on and offline. The primer scope with broad brushstrokes to the relationship between human rights and the digital domain. The hope is to create awareness and spark a broad discussion on how to extend our fundamental human rights into the digital domain.

Part 1, covering: Introduction, The Digital Domain and Human Rights, Our Digital Identity, Integrity and Dignity, Access, Rights and Duties, is available here.

Part 3 of the Primer to be published in 2 weeks, will continue on the topic of our digital identity and address topics such as: “Governance, The digital Domain on its way to Statehood , A Bill of Digital Rights and Responsibilities.

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byRadix

Sponsored byDNIB.com

Sponsored byIPv4.Global

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byCSC

Sponsored byWhoisXML API