|

||

|

||

At last week’s Chinese Internet Research Conference, much discussion of the “myths and realities” of the Chinese Internet revolved around images, metaphors, and paradigms. In his award-winning paper titled The Great Firewall as Iron Curtain 2.0, UPenn PhD Student Lokman Tsui argued that “our use of the Great Firewall metaphor leads to blind spots that obscure and limit our understanding of internet censorship in the People’s Republic.” (The paper and powerpoint will soon be posted on the Circ.Asia website.) It’s a catchy term, combining “great wall” and “firewall” to characterize the Chinese government’s effort to control the Internet, while at the same time conjuring a similar kind of image in our minds as the cold-war term “iron curtain.”

Reliance on the term “great firewall of China” causes outsiders (especially Americans and Western Europeans) to think mistakenly that the main battle that needs to be fought in order to bring freedom of speech to the Chinese people is to “tear down that wall”—and enable all the good stuff (i.e. “truth”) from the outside to get in. The reality, of course, is much more complicated. As anybody who studies (or experiences) Chinese Internet censorship can tell you, the system that filters or blocks external websites from internal view (which in itself is imperfect and full of holes) is only one part of a complex set of mechanisms—and social behaviors—that actually determine how much “free speech” Chinese internet users manage to have or not have. There is a vast system of internal censorship, mainly carried out by the private sector, as well as the seeding of online conversations to encourage them in certain directions and not others. There are also the nationalist “angry youths,” there is cyber-bullying, there are flame wars, and “human flesh search engines” (cyber-vigilantes)... not to mention all kinds of porn and rampant distribution of copyrighted works. Among other things. Tsui argues that the “great firewall” metaphor has governed U.S. information policy to such a degree that it leads to policies that do not fit well with China’s reality, and thus are unlikely to be successful if not counterproductive. He cites the Global Online Freedom Act and its predecessors as one particular example.

Jeremy Goldkorn of Danwei.org prefers the term “net nanny” when discussing Chinese Internet censorship. He points out that this parental image is more in keeping with the way that Chinese authorities in charge of regulating the Internet describe their own jobs, and also in keeping with the way that many Chinese appear to view the system. As Deborah Fallows pointed out in her presentation, a recent survey of Chinese Internet users in seven major cities found that “over 80% of respondents say they think the internet should be managed or controlled, and in 2007, almost 85% say they think the government should be responsible for doing it.” There is apparently a feeling among many Chinese Internet users that things are out of control, that there’s much misinformation, violence, and porn, and that they would like their children as well as themselves to be protected from it to some degree. One of our presenters, Anne Cheung, a law professor at my own university, presented a long litany of nasty cyber-bullying cases that have taken place over the past year and advocated that ISP’s need to get more nanny-like in order to bring cyber-bullying under control. (This proposal was not popular with bloggers in the room.)

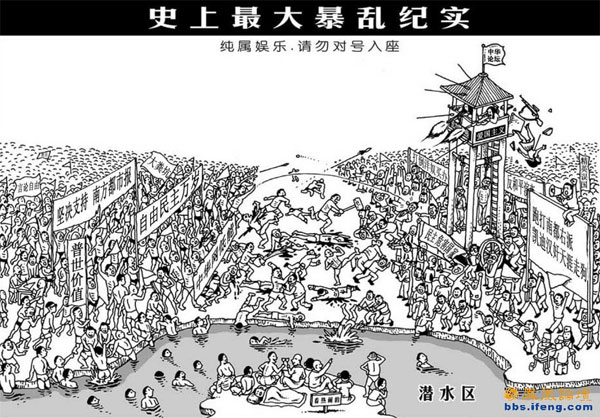

Which brings me to the next image:

Both Roland Soong and Isaac Mao independently put this cartoon in their Saturday afternoon presentations (see summaries of those presentations courtesy of the indefatigable Dave Lyons and John Kennedy here and here). The cartoon is titled “The Recorded History of the Biggest Riot in History.” On his blog, Roland explains it as follows:

This is a cartoon about the Internet battle between users of China.com and supporters of Southern Metropolis Daily over Chang Ping’s opinion essay How To Find The Truth About Lhasa?. On the left, the slogans are: Freedom of speech; firmly support Southern Metropolis Daily; universal values; defecation ditch (referring to China.com as a collection of shitty angry young people); long live freedom and democracy; China.com is retarded. On the right, the slogans are: the elites are ruining the country; chase away the rightists at Southern Metropolis, the Chinese traitors at the KDnet forum and the running dogs at Tianya forum; oppose peaceful evolution; down with foreign lackies and compradores; democracy puts the nation in danger. The ocean is known as the “underwater” area in reference to netizens who only read and never write. The little island is for the spectators. The disclaimer under the title on top says: Purely for entertainment and one should not think that this was about any particular person.

In Roland’s account of the session with Isaac, he repeats a point made by Isaac that “this drawing showed a static situation when in fact the situation was evolving dynamically over time. The fact that opinions were shifting meant that there was significant debate and interaction, and this drawing only provides one cross-section at a particular moment in time of an ongoing process.” I quote Roland’s descriptions and discussion of this picture at length for a reason: If your understanding of the Chinese Internet is based primarily on the “great firewall” metaphor, this picture—along with the online debates and flame-wars that inspired it—cannot compute. Depending on where you sit, the Chinese Internet may seem like a place where people are suppressed, censored, and controlled; but from some other people’s vantage point it seems like a chaotic free-for-all. Or, if you can handle cognitive dissonance (which comes naturally if you’ve lived most of your life in mainland China), it’s both at the same time…

Yet another metaphor was brought up in the final session of the conference: our “all star” panel of Chinese journalists and editors. Dr. Li Yonggang formerly of Nanjing and now at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, whose influential scholarly website “Horizons of Thought” was shut down after 13 months in operation, said he thinks the government’s efforts to “manage” the Internet can be best described as a hydro-electric or water-management project. China’s current crop of leaders come primarily from a technocratic, engineering background, and thus they apply their engineers’ perspective to governance. If you approach Internet management in this way, the system has two main roles: managing water flows and distribution so that everybody who needs some gets some, and managing droughts and floods—which if not managed well will endanger the government’s power.

It’s a huge complex system with many moving parts, requiring a certain amount of flexibility—there’s no way a government can have total control over water levels or water behavior. Depending on the season, you allow water levels in your reservoir to be higher or lower… but you try to prevent levels from getting above a certain point or below a certain point, and if they do you have to take drastic measures in order to prevent complete chaos. The managers of the system learn as they go along and adjust their behavior accordingly. It is a very resource-intensive enterprise in terms of people, money, and equipment, but while some functions are delegated to the private sector the government doesn’t feel comfortable privatizing the whole thing, for fear of loss of control (and power). Li emphasized that with so many parts, and with the involvement of several different ministries, government bodies, and private companies, it would be wrong to view the behavior of this system as monolithic or centrally controlled. To some extent, the system once built has a life and logic of its own that propels it to continue, with a whole economic food chain of vested interests springing up around it.

What’s tough for many Westerners to get their heads around is that on the Chinese Internet all of these metaphors can be true simultaneously. The “great firewall” is not a total myth—it’s indeed a fact that China has the world’s most sophisticated system of Internet filtering. But that is only one part of a very complex and often contradictory, confusing whole.

Sponsored byIPv4.Global

Sponsored byCSC

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byRadix

Sponsored byDNIB.com

Sponsored byWhoisXML API

Sponsored byVerisign