|

||

|

||

Rainy London in March by Dirk Ingo Franke

Rainy London in March by Dirk Ingo Franke

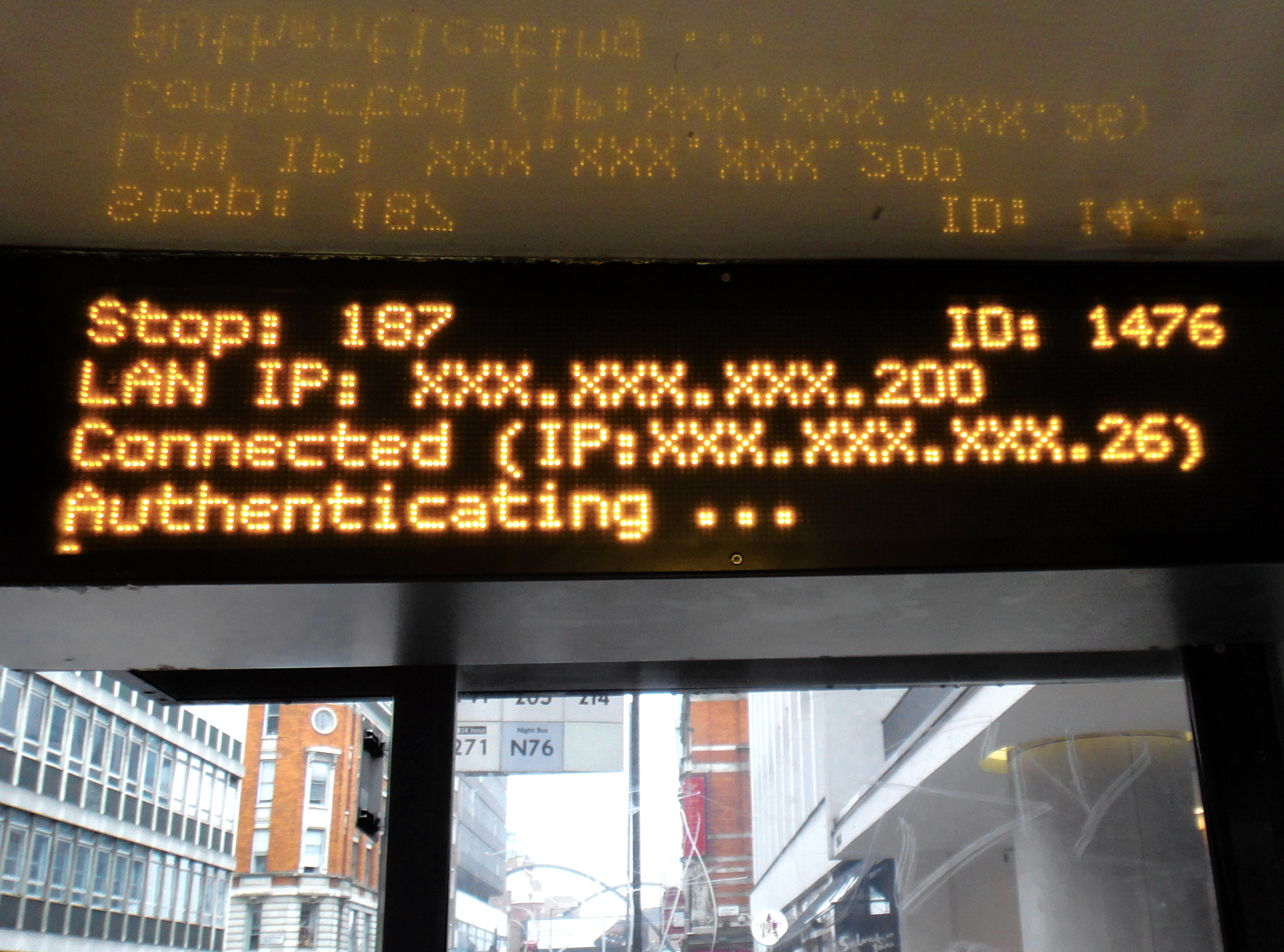

Photo: WikimediaI always geek out a little when I see something ICANN-related breaking out into the real world, like when the bus-stop display has borked, and its LAN is vainly searching for an IP number so it can reboot.

Or the ICANN Paris meeting back in 2008 when the board gave the thumbs up to the GNSO policy to launch new gTLDs. One day we were an obscure Californian organisation doing something technical-seeming most people had never heard of, and the next we were working two phones each, giving journalists quotes and information for dozens of front-page news stories around the world. It was exciting and just a little weird to see what ‘normal people’ made of the huge change to the DNS the community and staff had worked on for years.

Since 2014, when the geographic names TLDs—.berlin, .capetown, .alsace, .quebec, etc.—started to launch, I get frequent, geeky little thrills from seeing city and regional names on poster-hoardings out in the wild. My sister’s favourite yoga studio is www.yogarise.london in Peckham, just down the road from me. Peckham is one of the most vibrant parts of London, and YogaRise is a cherished and thriving business that does things a little differently and contributes to good causes, locally. It makes total sense to me that YogaRise would choose a dot london domain. It signals that they’re local and innovative, both rooted in our community and determined to do and try new things.

So I already had a lot to say when Dirk Krischenowski from geoTLD.group asked if I’d like to write something about how the geo’s are doing, four years post-launch. It’s been quite a journey.

It seems almost unbelievable now—because all great ideas become ‘the new normal’ very fast—but when Dirk started doing the rounds of ICANN meetings in 2005, selling the idea of city and regional TLDs, I didn’t really get what it meant. Why would cities have TLDs? And regions? Don’t we already have country codes for that? (FYI, I saw a pitch from eBay in Brussels in about 1999, and instantly thought ‘this will NEVER catch on’.)

But now I get it. We’re living in a moment when our loyalties and identities are shifting, and nation-states can seem far-removed from the realities of our lives. Though I’ll never be British (thank you, Brexit), I sure as hell am a Londoner. So when I see a dot London domain, it appeals directly to me with a mix of tribal loyalty and tech innovation that makes me want to put my hand in my pocket and buy something. This stuff is marketing rocket fuel, because it’s a real, not manufactured feeling. And I’m clearly not the only one who feels this way.

A quick look at the stats shows the top five of the fifty-one geoTLDs delegated so far are Tokyo, London, New York, Berlin and Amsterdam; five of the world’s most coveted and exciting places to be. These ‘magnet cities’ draw huge numbers of talented and ambitious people, and drive so much of our global culture. But they’re also fiercely local, loyal and proud. So, of course, they would be early adopters of city names.

What’s really interesting is how the geo’s stand out from many other new gTLDs, especially the ‘dot word’ ones. geoTLDs have the lowest rates of parked domains—used typically for speculation and intellectual property protection—and higher rates of people associating the names to real websites.

Kieren McCarthy wrote on this website a while back that while registrations and renewals are a somewhat useful way to measure a registry’s progress so far, to figure out its chances of future success, you need to look deeper at how (let’s be honest, ‘if’) people actually use the domains: ”... future success—for both registries and registrars—mostly likely lies in two things: high rates of renewal and future growth potential.” The geo’s tend to have low parking and high use. They’re out in the wild, on poster hoardings, business cards, shop windows, Instagram; everywhere people are doing interesting and useful things in the real world.

CENTR’s recent report found that a “third of all new gTLDs (2012 ICANN application round) have contracted over the past 12 months.” We’ve all heard horror stories about low renewal rates in some new gTLDs. But geoTLDs are steadily growing, at 1.9% year on year, which is comfortably higher than the growth rate of the global TLD market; 1.4% by Q1 2018.

Now, that same report tells us the global number of domain names is about 330 million, so as geoTLDs account for less than a million of those, they’re not going to be eating .com’s lunch any time soon. But that’s not the aim.

Some geoTLDs are very small, but their sponsoring organisations seem satisfied as their strategy is to closely manage the domain and the brand identity of the region or city. For example, .stockholm has a startlingly low number of names registered. But though it hopes to widen the registration criteria and open up to the broader Stockholm region, the registry says it’s never going to be a .NYC. Its ambitions are more Brussels-sized, aiming for 5 – 7,000 names.

And then there’s .EUS, the geoTLD for the Basque region. Its registration total is a bit over 8,000, but the registry guesstimates this could be more than two thirds of the total number of businesses in the region. Loyalty to .EUS is unsurprising, given how strong Basque feeling can be, but it shows how much latent demand there was for domain names that match many people’s regional identities.

The geo’s are that rare thing in a DNS originally built as a taxonomy of how the world seemed to American engineers in the 1980s and early 90s. (Remember, out of the 6 historic TLDs, only three were open to non-US organizations.) The geo’s represent the world as many of us experience it, and not as the DNS originally tried to organize it. We largely live in cities and are often more interested in goods and services we can trust and access nearby, or we work for local instances of global companies, like publicis.london.

(Hint: if you want a real-life check of whether our loyalties are more local and regional than national, ask people which football team they support.)

Why are the geoTLDs bucking the overall new gTLD trend and doing surprisingly well (albeit in a fairly low-key way)?

Firstly, because geo’s have a clear market and strong motivators; the way we feel about who we are, and the ties we feel to those around us. In a globalised, tech giant world, geo’s are unashamedly rooted in real-world communities. They also serve the business need for domain names that are both available and meaningful. Much growth and churn in wider economy comes from new, small businesses and independent contractors. And while some people dream of launching the next Google or Skype, most businesses stay fairly small—think hairdressers, builders, graphic designers. They’ll always need names and to be able to quickly and cheaply target their markets and communicate their brands.

Secondly, as the dot London blog pointed out, geoTLDs may have been helped by a stroke of sheer luck. An update to Google’s Pigeon algorithm in 2014 meant search results close to the user’s location moved up the rankings. Now, Google’s public position on its search algorithms is a bit like the British royal family; ‘never complain, never explain’, so it’s impossible to be sure. But it looks like geo-names, along with country codes, are used by Google to infer content is local, which means users are more likely see geo websites at the top of the results. That’s made them even more attractive to local enterprises.

I expect geoTLDs will continue to grow steadily, if not spectacularly. People want relevant, trusted, local names, and as many countries seem increasingly fractious and divided, our local loyalties can only strengthen. Medium and longer-term, geoTLDs will be both the rallying points and the beneficiaries of the innovation drive of our cities, the strong identities of our regions, and the more tribal ways we now see ourselves.

I can’t wait to see .dublin.

Written by Maria Farrell, in conjunction with www.geoTLD.group

Sponsored byRadix

Sponsored byDNIB.com

Sponsored byWhoisXML API

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byCSC

Sponsored byIPv4.Global

Sponsored byVerisign