|

||

|

||

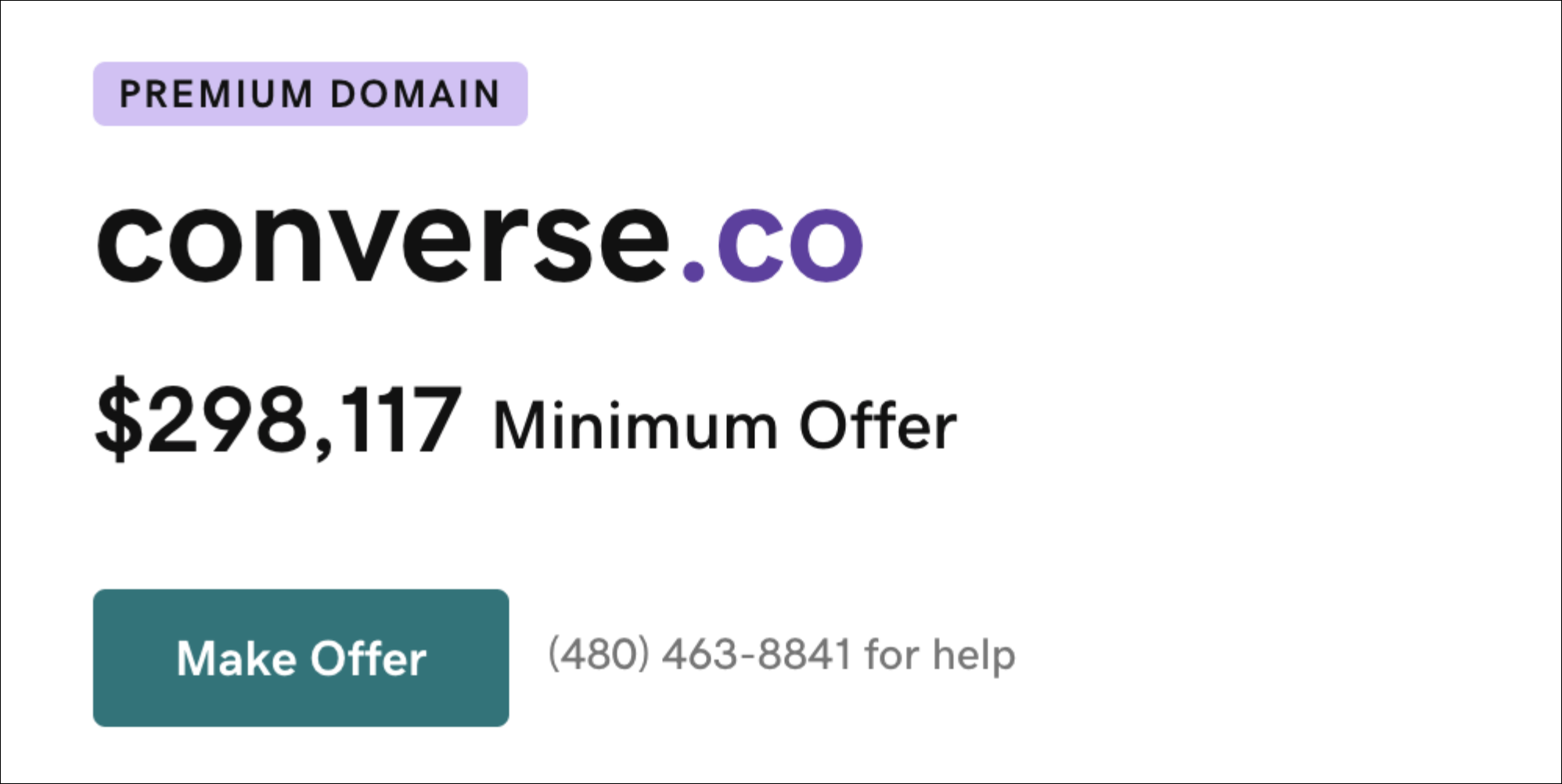

In the Converse.co dispute, (All Star C.V., Converse, Inc. v. Narendra Ghimire Case No. DCO2024-0014), a three-member UDRP panel unanimously ordered the transfer of the disputed domain name to the Complainants, All Star C.V. and Converse, Inc., owners of the well-known brand CONVERSE for shoes and apparel. The panel drew the inference that the Respondent, by setting an asking price of around $300,000 after having acquired the domain name for $306, was primarily motivated by a bad faith intent to target the Complaint.

The Converse.co dispute is directly on the fault line created by the different perspectives of a domain investor and a brand owner as to what is, or is not, permissible under the UDRP. It would make a great moot UDRP session, in the model of the one on redball.com from 2021 that was jointly presented by INTA and the ICA (excerpt here), as both sides can make strong, well-supported arguments, as indeed they did here.

Elliot Silver articulates a domain investor’s view of the case in his blog post, Converse.CO UDRP Decision Turns on Price Inference. As Silver wrote:

My interpretation is the panel believed that the price was set high enough that the only realistic buyer would be the well-known Converse brand. In my opinion, this is flawed thinking.

As a domain investor, I would look at it another way. If I owned Converse.CO, I would imagine Converse would have little interest in the lesser value .CO domain name. If you already have the .com, you don’t need the .CO. I would also assume that any company that wants to brand itself as Converse.CO—an AI or other similar type of company—would understand potential risks of sharing a brand space with Converse. They would know their offering needs to be distinct from the sportswear and shoe company, and they would also know there could be a legal battle. This type of buyer would have ample funding and a legal war chest to protect the brand they are building. As such, a company interested in creating a different Converse brand would be able to pay the ask. Additionally, it is an asking price and perhaps the number to get it done is lower.

In general, domain name investors believe that UDRP panelists have no business evaluating whether the price of a domain name is realistic or not. Most UDRP panelists have no expertise in domain name valuations. Domain name valuation is challenging even for the most experienced domain name investors. It does not help that there is very little transparency as to the high end of the market, as nearly all high-dollar transactions are covered by non-disclosure arrangements so that the purchase prices are never publicly disclosed. For instance, a domain name broker recently shared that he had helped facilitate a $2 million sale, yet could not reveal the domain name.

Panelists can easily get tripped up when they presume to draw inferences from the asking price of a domain name, as did all three members of the panel in the ADO.com dispute from 2017. The ICA’s statement on the decision noted:

In the recent ado.com UDRP decision, the panel made the speculative and factually incorrect finding that a “high” asking price indicated bad faith targeting of a trademark. The UDRP is intended to address clear-cut cases of cybersquatting, not to second guess the asking prices set on inherently valuable domains in an open and competitive marketplace. This overreaching decision undermines ownership rights to domain names as an investment asset class and destabilizes the multi-billion-dollar aftermarket in domain names.

Indeed, after an expensive court battle forced on the domain registrant by the panel’s decision to transfer the domain name, the registrant was validated in a settlement that recognized that the registrant’s ownership of the ado.com domain name was lawful.

Yet, from a brand owner’s perspective, a very high asking price can be useful evidence as to the respondent’s intentions in registering the disputed domain name. If the asking price is only plausible if it is targeted at the brand value created by the brand owner, then the price can be seen an indicator as to whether the registrant registered the domain name due to its value as a dictionary word or generic phrase, or instead due to classic cybersquatting on the goodwill created by the brand owner.

The language of the UDRP, in section 4(b)(i), requires a panel to ascertain whether the respondent acquired the disputed domain name “primarily for the purpose of selling” it to the Complainant. Where the Complainant’s brand is based on a widely used dictionary word like “converse”, the most salient evidence in drawing an inference as to whether the registration was “primarily for the purpose of selling” the domain name to the Complainant may be the asking price. This is the position taken by the Panel, which states that “the price is a window into Respondent’s probable intent.” From this perspective, a panel would be remiss in failing to draw reasonable inferences from the asking price.

Yet, as discussed above, attempting to draw reasonable inferences from an asking price places the panel in a very fraught situation. In Converse.co there was no direct targeting. Although the landing page hosted by the Afternic marketplace was merely a contact form, a search on the Afternic website indicates that the asking price is nearly $300,000.

While the Complainant is the dominant user of the Converse mark, it is not the only user. When I search “converse” on Google, the first page of results also includes results for Converse University, the dictionary definition of “converse”, the City of Converse, Texas, and Converse county, Wyoming. Converse University is reported to have an endowment of over $160 million and recently received a $10 million bequest. If Converse University wished to expand into for-profit arenas, for example, the Converse.co domain name might appeal to them and they apparently have the financial means to make a substantial offer should they so wish.

Moreover, the dictionary meaning of “converse” is inherently appealing and similar domain names have attracted high valuations. One of the most expensive domain names ever sold is Voice.com at $30 million. “Voice” and “converse” have related meanings. Similarly, Speak is a mobile app that has raised over $20 million and operates on the Speak.com domain name.

Converse.co could attract a substantial offer based on its dictionary meaning alone for a use unrelated to the Complainant’s sportwear and shoe offerings. Converse Health, which adopted the Converse.Health domain name, uses AI to help clinics communicate with their patients. This suggests that converse-formative domain names, including Converse.co, can be put to a wide variety of non-infringing uses.

Panelists have the challenging task of assessing evidence and drawing subjective inferences of bad faith from that evidence. In this sense, the UDRP functions as a smell test, as I wrote in “Smells Like Cybersquatting? How the UDRP ‘Smell Test’ Can Go Awry”. In the article, I explain that since domain name investors in general only sell such a miniscule percentage of our portfolio each year, the only way the business model works is if domain names can realistically be priced at a high multiple of the acquisition cost, such as 5 times to 20 times the purchase price:

Only in this way can the very small percentage of domain names that sell each year generate sufficient revenue to make it a viable business. As a rule of thumb, an investor will usually be willing to commit $1000 to acquiring a domain name only if she believes that it can sell for between $5,000 to $20,000 or more.

The trouble that panels can get into by their lack of knowledge of the domain investor business model and by making misguided inferences from an asking price is demonstrated in the victron.com dispute from 2022, where the disputed domain name was transferred over a dissenting view. In the victron.com dispute, the Respondent acquired the domain name for $7,000. The majority held:

The Respondent has not specified the exact amount that it was looking for as price of the disputed domain name. A 5-figure amount would be anywhere between USD 10,000 and USD 99,999. Even if the lowest figure is taken, it would still make a 43% profit, and will be well in excess of the Respondent’s documented out-of-pocket costs directly related to the acquisition of the disputed domain name, which it states were equal to USD 7,000.

Yet a domain name investor acquiring a domain name for $7,000 and then offering it for sale for $10,000 is not evidence of targeting the complainant. An investor would promptly go broke buying domain names for $7,000 and selling them for $10,000 given that a sell-through rate of 2% is considered desirable. The reasoning in victron.com demonstrates the perils of incorrect inferences from an asking price.

Yet, despite the long odds and all the risks inherent in a panel’s attempt to draw inferences from an asking price, the converse.co decision is, in my view, a rare instance where the panel’s “smell test” may have worked and its inference may have been justified. As I mentioned in the “Smell Test” article above, given the very small chance that any specific domain name will find a buyer, investors usually require the possibility of a 5x to 20x return when acquiring a domain name at auction to justify the purchase. Conversely, what this means is that in a competitive bidding situation, the bids will often reach 1/5th to 1/20th of the expected end-user sales price. Sometimes investors get lucky, especially on domain names acquired for $500 or less, and may be able to resell the domain name for a 50x or 100x multiple. Yet it would be extremely unusual for a domain name that had a recognized resale potential of $300,000, based solely on the inherent appeal of the domain name, to fetch only $306 such that it sold for 1/1000th of its potential resale value. Yet that is what the Respondent claimed happened with converse.co.

That such a scenario is quite unlikely suggests that the inherent value of the domain name is far less than $300,000. It also suggests that by setting an asking price of $300,000, the Respondent could reasonably be inferred to have targeted the value of the goodwill created by the Complainant. The Panel took a similar view:

The Panel notes that Respondent has disclosed it purchased the Disputed Domain Name for USD 306, and, the Panel simply finds it implausible that Respondent immediately directed the Disputed Domain Name to Afternic, placing it for sale for approximately USD 300,000, merely in consideration of the dictionary value of the term “converse”.

The Panel likely does not have sufficient familiarity with the domain name aftermarket to rely on reasoning such as I offer above, yet let’s say for the sake of argument that in this dispute the Panel made a reasonable inference of bad faith due to the asking price. Yet even if the Panel got it right in this instance, this does not mean that most panels can avoid being tripped up by the numerous pitfalls they face in attempting to make inferences of bad faith due to an asking price.

The word “converse” is registered in nearly 300 TLDs, most apparently unconnected to the Complainant, and many offered for sale by domain name investors. What if the sales price of a “converse” domain name in one of these extensions instead of being $300,000 was $50,000, or $10,000 or $5,000? It places a panel in an untenable position of having to determine at what point an asking price is more likely than not based on the complainant’s goodwill in its mark rather than on an optimistic assessment of the inherent value of the domain name. Each panelist will make this subjective inference differently. This showcases the limitations of this approach and that it is ultimately a dead end.

It is no surprise that the “primarily for the purpose of selling” language found in the UDRP is over 25 years-old, and dates from an ancient era where there were still only a handful of TLDs, where classic cybersquatting of the dot-com domain names of famous brands still occurred, and when domain name investing was in its infancy. It is ill-suited for the current reality of a mature aftermarket in domain names and where a second level domain name based on a common word or phrase that is also an exact match to a well-known trademark can be registered in hundreds of different TLDs by a large number of unrelated owners.

The underlying goal of the UDRP is to protect brand owners from harm. This raises the question of how the Complainant was harmed by the Respondent acquiring Converse.co and offering it for sale for around $300,000. The Complainant uses Converse.com and has no need of the .co extension. If the Complainant is correct that the domain name does not have a value of $300,000 to any third-party, then the domain name will sit unsold, harming no one. If the Complainant is incorrect, and an unrelated start-up successfully negotiates to acquire the domain name for a non-infringing purpose, such as Converse Health does with its Converse.Health domain name, then again, the Complainant is not harmed.

A flaw with the UDRP is that it relies on a highly subjective assessment of bad faith intent rather than an objective assessment of whether the Complainant is being harmed. Is it fair that Ovation.com is lost in a UDRP because the registrar placed a PPC link that referenced one of the Complainant’s products on a landing page? Does the Respondent deserve to lose a domain name it acquired for a substantial sum due to PPC ads that generated perhaps $10 in revenue to the registrar? There can be an enormous disproportion to the major harm inflicted on a Respondent to avoid a negligible alleged harm to a Complainant.

Sponsored byWhoisXML API

Sponsored byCSC

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byRadix

Sponsored byDNIB.com

Sponsored byIPv4.Global

Sponsored byVerisign