|

||

|

||

The “Decoding Internet Governance Stakeholders” series of articles invites the community to ponder what underlies the labels that define our interactions, roughly 20 years after the “Tunis Agenda for the Information Society” called for the “full involvement of governments, business entities, civil society and intergovernmental organizations”, as well as to “make full use of the expertise of the academic, scientific and technical communities”. This series questions whether these labels are as meaningful as they were once purported to be, not aiming to reach conclusions, but rather to analyze what each label was intended to represent and the current reality of each stakeholder group.

This article benefits from newly conducted interviews with early members of the ICANN Business Constituency, now permanently archived on ICANNWiki. The interviews can be read here: Ron Andruff, Philip Sheppard.

The private sector’s involvement in Internet governance has its roots in historical partnerships with governments to develop large-scale communication infrastructures, such as telegraph and telephone networks. Governments often lacked the expertise required to efficiently build and manage these systems, leading to frequent collaborations with private companies. This model carried over into the digital age, where businesses are not only the main connectivity providers, but also develop many of the products and platforms that engage users online. Early involvement within ICANN was led by telecom companies and intellectual property lawyers, reflecting concerns over both infrastructure and legal matters. Gradually, general interest businesses became more prevalent, with the balance between the representation and participation of small and large companies being an early concern that has surfaced at different times during the evolution of the various Internet governance processes.

The private sector gradually rose in importance in telecommunications, particularly with the global integration and subsequent liberalization of communication networks. As the sector shifted from being composed of monopolies (both State-run and privately held) to a more competitive environment, these actors continued to expand their services, eventually becoming central players in the emerging digital space.

In parallel, a number of telecom and early computing companies had already been actively participating in pre-Internet governance bodies that helped establish several of the field’s technical standards, such as the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), particularly within the Consultative Committee for International Telephony and Telegraphy (CCITT), which is now the ITU-T (Mansouri, 2023).

In fact, the proto-Internet community formed the International Network Working Group (INWG) in 1972 counting with representation from the private sector, governments, and the technical community to develop a universal standard for internetworking. Their packet-switching proposal, however, threatened the prevalent telecom business model (Day, 2016).

With a membership stacked with governmental telecom monopolies, the CCITT rejected the proposal, leading INWG Chair Vint Cerf to resign and focus instead on developing what would become TCP/IP. A split ensued between a smaller U.S.-backed ARPANET group and a larger one based in Europe seeking a more formal venue for their efforts (Russell, 2013).

Starting in 1977, the group pursued development of the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model at the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). OSI was elegant in its intended design, but relied on a rigid and bureaucratic development methodology, resulting in the reference standard being published only in 1984, by which time TCP/IP had undergone several iterations and real-world testing.

Tech giant IBM’s market dominance granted it control over protocols, making its inclusion in the deliberations key to avoiding vendor lock-in. However, the alignment of interests between IBM and the CCITT in preserving the existing telecom business model shaped much of the initial discussions, which slowed progress. Combined with the multitude of parallel OSI work tracks, committees, and need to accommodate hundreds of voices, the process dragged on into the 1990s (Day, 2008; Day, 2016).

TCP/IP, operating over packet-switched networks, became the de facto Internet standard after a series of events already better covered in our previous article concerning the technical community. In the aftermath, “[those] with experience of the ITU realised its decision-making process was too slow for the fast-evolving Internet and lobbied for something else” (Sheppard interview, 2024). Partially in response to such concerns, ICANN emerged from a series of compromises between the U.S. government and the Internet governance community.

The business sector was included from the outset, as the “Commercial and business entities”, “ISP and connectivity providers” and “Trademark, other intellectual property and anti-counterfeiting interests” constituencies (ICANN, 1999). Many of the founding members of what later became the Business Constituency (BC) were telecom companies, demonstrating a continuity of interest from their previous efforts.

Both the profusion of business representation in the community’s structure and the heavy presence of telecom operators were in large part due to the efforts of AT&T’s lobbyist and BC founder Marilyn Cade (Cade interview, 2020 by Férdeline; interviews from this project). Meanwhile, the “non-commercial domain name holders” constituency was the only representative of that stakeholder.

The business community’s early involvement in ICANN focused on addressing the Internet’s original design philosophy, which had prioritized technical functionality over market considerations such as trust and consumer protection. This soon led to contention over the transparency of the WHOIS database, an issue that remains only partially resolved to this day.

Businesses pushed for access to WHOIS data to aid in legal and law enforcement efforts, while privacy advocates argued for a right to anonymity, and contracted parties were concerned about limiting financial impacts. Additionally, the creation of a Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy (UDRP) quickly became a priority.

Another concern was that the ICANN organization was established with minimal resources. ICANN’s small staff faced role accumulation, and the information needed to properly formulate policies was better understood by the supplier side (contracted parties) than the client side, with not enough policy experts within the organization to support the community. Early BC member Ron Andruff proposed at ICANN 12’s Public Forum that ICANN should take in 25 cents per domain name per year to solve these issues—a model which is still the basis for the current one (Andruff interview, 2024; ICANN, 2002; interviews from this project).

Meanwhile, the business sector’s participation in the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) grew significantly as the Internet moved toward commercialization. Initially, companies directly involved with the ARPANET project were in attendance, such as BBN, Cisco, and IBM. By the 1990s, the IETF had transformed into an international standards-making body where business interests played an important role, collaborating with government and academic groups to shape critical Internet infrastructure that supported the emerging global network economy (Rutkowski, 2021 at CircleID).

Around that time, the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) established itself as the hub for Web standards, drawing significant participation from the private sector due to the growing importance of online commerce. The W3C community spearheaded the development of early versions of HTML, as well as CSS and other building blocks of the Web. Research into contributions to W3C standards found that businesses of all sizes, including small enterprises, were the leading contributors over time (Gamalielsson & Lundell, 2017).

As far as ICANN is concerned, it is reasonable to affirm that the distinction between the BC, the Intellectual Property Constituency (IPC) and the ISPs and Connectivity Providers Constituency (ISPCP) has become clearer with time. The analysis below was carried out by the author, looking into public records of BC membership in 2001 and 2024. The assignment of categories was arbitrary, based on each company’s stated mission. This revealed interesting trends about business participation in Internet governance in general:

| ICANN Business Constituency membership by category (2001 vs. 2024) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Category | 2001 | 2024 | Difference |

| Telecommunications | 10 companies | 2 companies | -8 |

| Technology & Electronics | 9 companies | 22 companies | +13 |

| Associations & Trade Organizations | 16 organizations | 8 organizations | -8 |

| Media, Entertainment & Consumer Goods | 6 companies | 6 companies | 0 |

| Transportation & Logistics | 3 entities | 1 company | -2 |

| Financial & Professional Services | 4 companies | 16 companies | +12 |

We can observe a migration of the telecom sector from the BC to the ISPCP or away from formal ICANN participation entirely, possibly focusing their efforts on national governance. Additionally, there was a reduction in associations/trade organizations, some of which may have shifted interests to the IPC or now rely on more centralized points of contact such as the International Trademark Association (INTA).

Meanwhile, the number of technology/electronics companies saw a significant increase, reflecting the growth of platforms and Internet-based solutions. Additionally, financial/professional services companies have also grown substantially, driven by the increasing demand for consultancy and support services within Internet governance and adjacent areas, as well as the expansion of the digital economy.

A further data point was analyzed, focusing on the geographic distribution of BC member companies when comparing 2001 with 2024:

| ICANN Business Constituency membership by continent (2001 vs. 2024) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Continent | 2001 | 2024 | Difference |

| North America | 14 companies | 31 companies | +17 companies |

| South America | 2 companies | 4 companies | +2 companies |

| Europe | 27 companies | 8 companies | -19 companies |

| Asia | 3 companies | 5 companies | +2 companies |

| Africa | 1 company | 10 companies | +9 companies |

| Oceania | 1 company | 0 companies | -1 company |

While the increase in North American companies aligns with the concentration of digital businesses in the U.S., the decrease in European participation stands out. One potential explanation for this trend is the intensification of regulation in Europe, with data protection and privacy laws (among others) shifting the focus of European stakeholders toward compliance with regional regulations, reducing their engagement in the names and numbers space.

A positive phenomenon has been the emergence of African business participation. Delving deeper into the dataset, it is revealed that this is largely due to Nigeria’s private sector. This can be attributed to several factors, including the country’s expanding digital economy, increased Internet connectivity, and rapid growth of mobile services, which have driven the need for businesses to engage in shaping the policies that affect the sector. Nigeria’s role as a regional leader in West Africa likely also serves as a driver of this movement.

Another important and somewhat correlated data point is the increase in the representation of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) from around the world over time. Due to measures put in place from the BC’s inception, all members have equal weight in the group’s decision-making and voting, which is a plus for these companies. However, consistent engagement is a notable challenge due to limited resources and competing priorities that make it difficult for SMEs to justify the time investment required for a high-demand effort like ICANN.

Moreover, business actors are often presumed to have the necessary financial resources for engagement and attendance, meaning they typically do not receive the same support available to other stakeholders. SMEs that do remain active often have a focused business interest, aligning their participation with specific goals. The growing number of financial/professional services companies within the BC offsets this to a significant degree, as there is a more tangible connection between business objectives and ICANN participation.

Meanwhile, large technology platforms and multinational corporations occupy a central position, much like the telecoms did in the past. However, from the perspective of current standards-setting bodies, their contributions are subject to checks and balances. It is their ownership of the platforms and of critical resources, such as undersea cables and cloud services, which grants them disproportionate influence over Internet governance. With this influence, though, comes increased regulatory scrutiny, particularly regarding data privacy, antitrust issues, and ethical responsibilities.

A final point of interest concerning ICANN that emerged from the interviews conducted for this series, and not only from the private sector interviewees, highlights a shift in the locus of conflicts within ICANN. In its early years, much of the tension centered around the relationship between the commercial side and the contracted parties, in a business-versus-business dynamic. However, following the division of ICANN into two Houses in 2009, tensions within the Non-Contracted Party House (NCPH) intensified, with a more pronounced commercial vs. non-commercial divide.

The false dichotomy that commercial and non-commercial objectives are inherently at odds has created friction and, at times, slowed down policymaking. To foster collaboration, intra-NCPH meetings were established as a platform for open dialogue. These meetings, which at one point became a separate event, were temporarily discontinued. However, they have recently been reinstated as a pre-ICANN meeting, encouraging both sides to work toward shared goals. This has led to improvements in intra-house relationships, shedding light on areas of consensus as well as potential pitfalls to be handled with care.

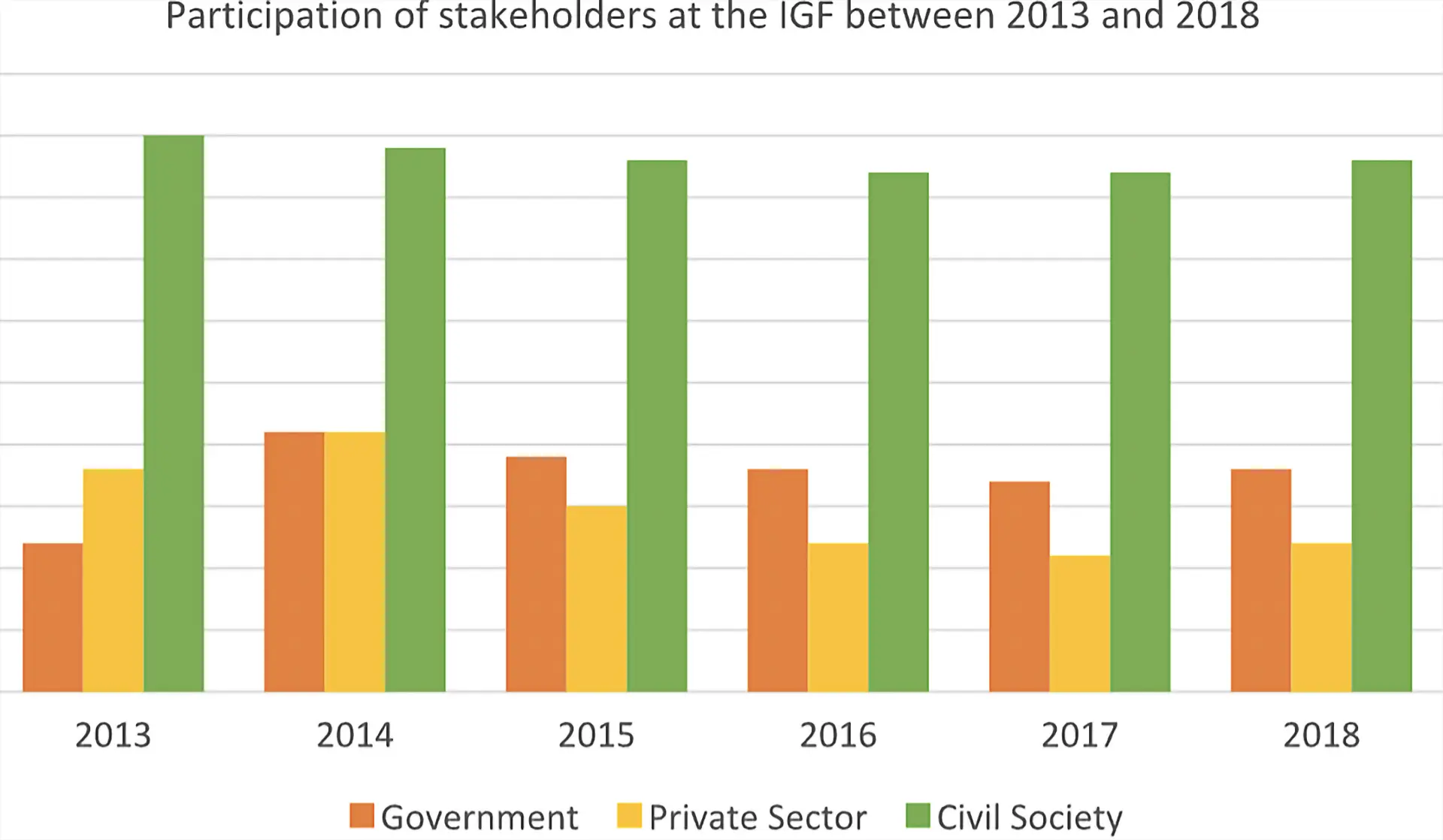

One final dataset worth mentioning, although unfortunately not fully up to date, is this comparison of stakeholder participation at the Internet Governance Forum (IGF), which highlights the lack of connection between the private sector and the event:

This pattern of low engagement from the private sector at the IGF, which seems to persist based on anecdotal evidence, raises concerns about representation. The absence of these stakeholders limits the community’s ability to develop solutions that not only advance research and public policy but also translate into digital products and platforms. A deeper exploration into the factors that hinder private sector participation and the potential strategies to foster their engagement is essential to ensure more actionable dialogue.

With these considerations, we can summarize that the private sector’s role in Internet governance has evolved significantly since its early engagement. While it has managed to maintain a strong presence within organizations like ICANN, its identity today is more diverse than in the past. Once dominated by telecoms and intellectual property concerns, the sector now includes SMEs, technology companies, and financial/professional services, each bringing different priorities to the table. This shift reflects broader changes in the digital economy, but it has also introduced new challenges. SMEs often struggle with resource constraints, while larger companies face increasing regulatory pressure and expectations of corporate responsibility. Looking ahead, the private sector’s ability to adapt to these pressures, participate effectively in policy development, and build consensus with other stakeholders will be critical to its ongoing influence in shaping the future of the Internet.

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byRadix

Sponsored byDNIB.com

Sponsored byWhoisXML API

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byIPv4.Global

Sponsored byCSC