|

||

|

||

Threat actors can often find targeting certain organizations too much of a challenge. So they need to go through what we can consider back channels—suppliers, vendors, or service providers. The Polyfill supply chain attack may fall into this category, as users with vulnerable content delivery network (CDN) service versions ended up with compromised networks courtesy of a malicious JavaScript code.

A polyfill is a piece of JavaScript code that enables older browsers to have modern functionality they do not natively support. A report on the attack revealed the perpetrators obtained popular polyfill open-source projects and infected the code by injecting malicious scripts into them. Users who downloaded compromised polyfills primarily on mobile devices were then redirected to scam sites.

Many cybersecurity researchers looked into the attack and identified indicators of compromise (IoCs). The WhoisXML API research team got hold of a list of six domains identified as such and examined them more closely to identify other potentially connected artifacts. Our IoC list expansion led to the discovery of:

A sample of the additional artifacts obtained from our analysis is available for download from our website.

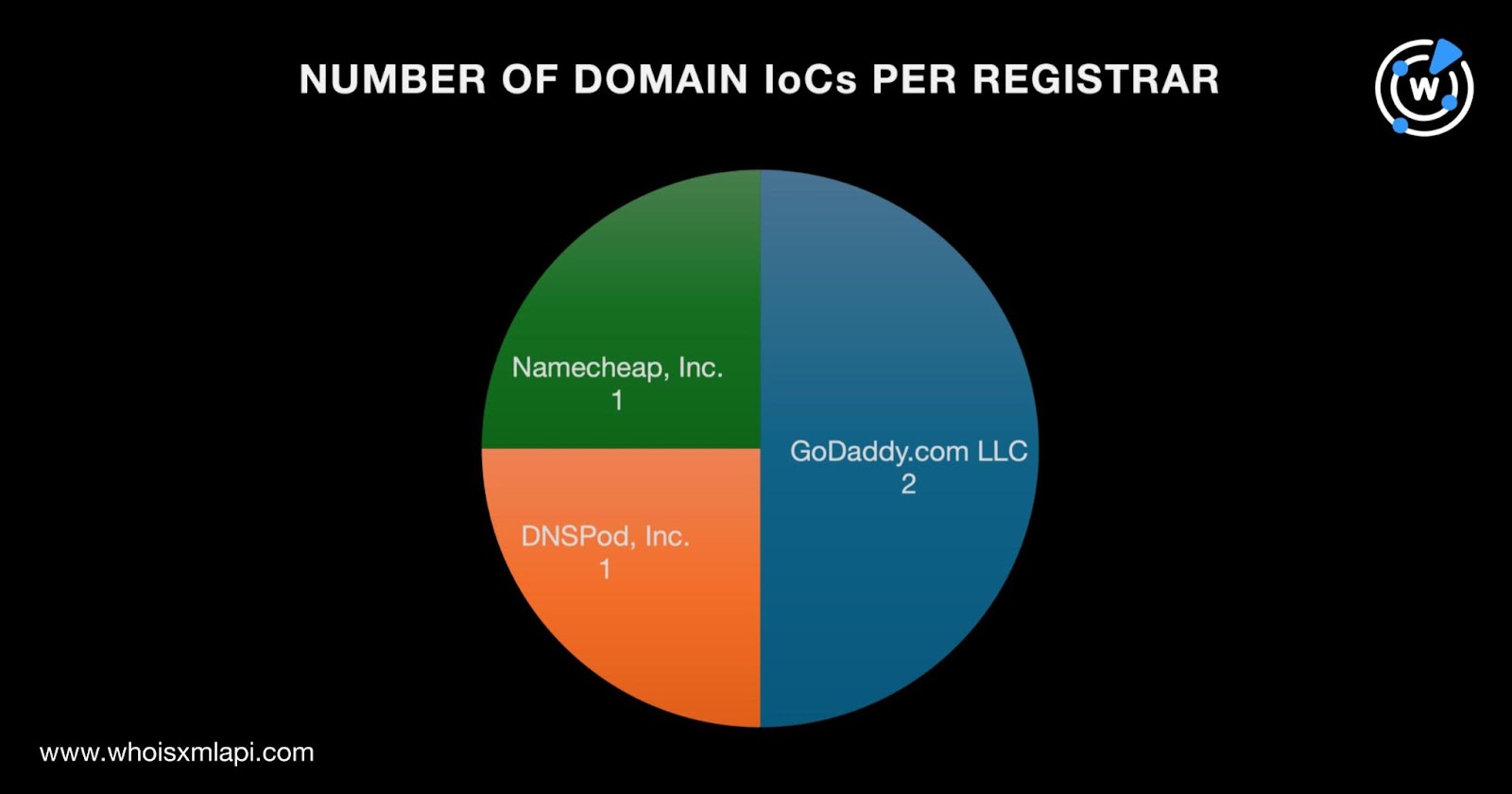

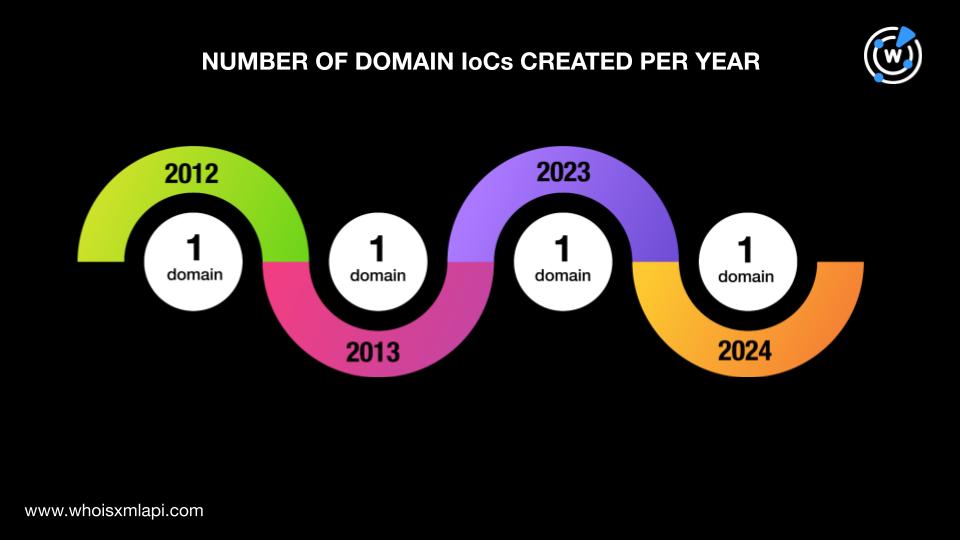

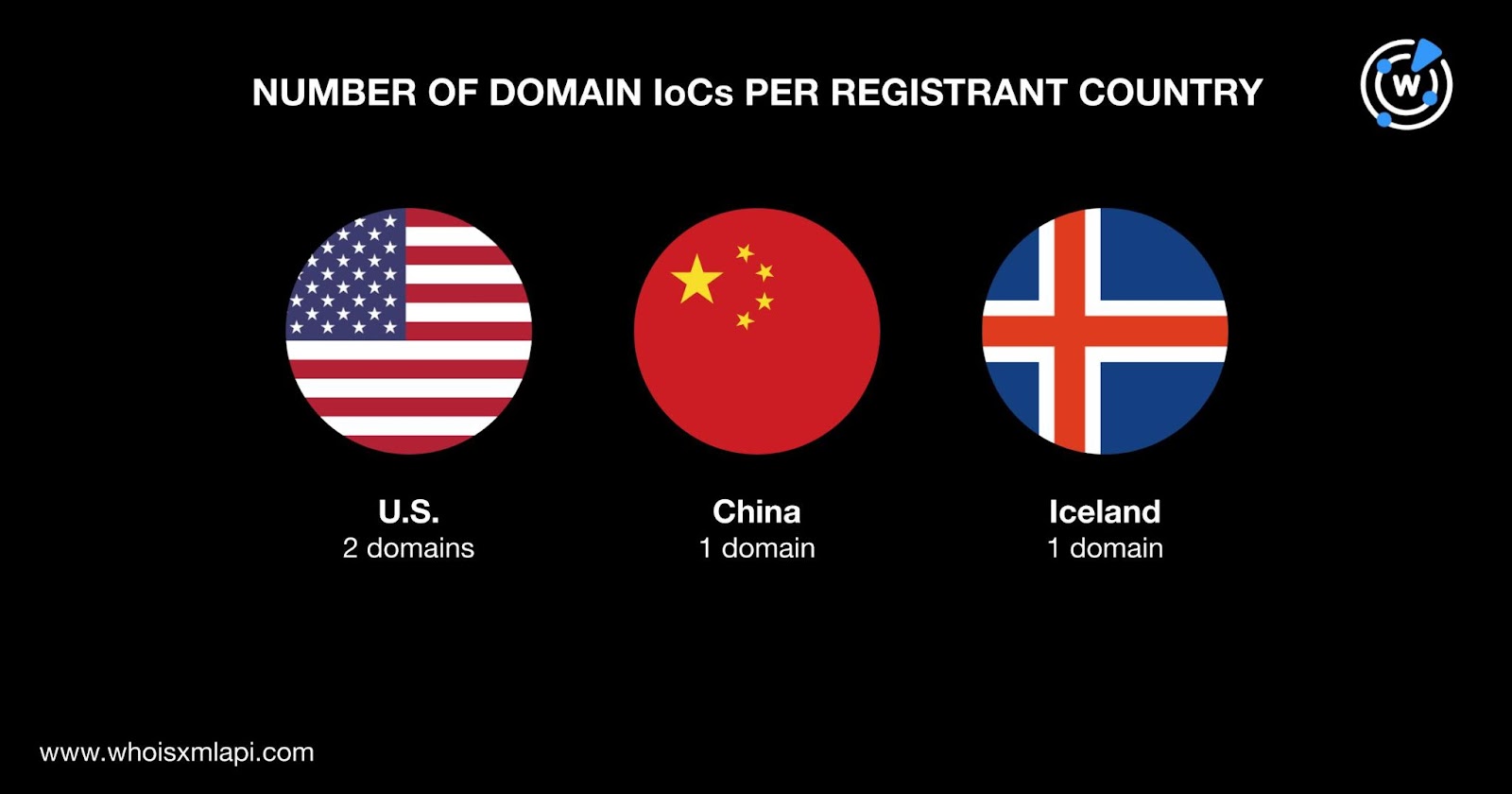

To gain a better understanding of the Polyfill attack infrastructure, we looked closer into the six domains identified as IoCs starting with a bulk WHOIS lookup, which revealed that:

The threat actors used a mix of newly registered and aged domains given that the IoCs were created between 2012 and 2024.

The U.S. was the top registrant country, accounting for two domain IoCs. China and Iceland accounted for one domain IoC each.

If there’s one thing all cyber attacks have in common, it’s that their perpetrators always leave traces behind. We sought to find such through an IoC expansion analysis for the February 2024 Polyfill supply chain attack.

We began by querying the four domain IoCs on WHOIS History API, which revealed the presence of four email addresses in their historical WHOIS records after duplicates were filtered out. Two of the email addresses were redacted while the other two were public.

Our Reverse WHOIS API queries for the two public email addresses showed that only one appeared in the current WHOIS records of other domains. However, given that the said public email address turned up in the records more than 10,000 domains, it could belong to a domainer.

This post only contains a snapshot of the full research. Download the complete findings and a sample of the additional artifacts on our website or contact us to discuss your intelligence needs for threat detection and response or other cybersecurity use cases.

Disclaimer: We take a cautionary stance toward threat detection and aim to provide relevant information to help protect against potential dangers. Consequently, it is possible that some entities identified as “threats” or “malicious” may eventually be deemed harmless upon further investigation or changes in context. We strongly recommend conducting supplementary investigations to corroborate the information provided herein.

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byCSC

Sponsored byWhoisXML API

Sponsored byRadix

Sponsored byDNIB.com

Sponsored byIPv4.Global

Sponsored byVerisign