|

||

|

||

In doing a recent search, there it was: the first White House website archived at the U.S. Archives. It ended up changing the direction of markets and network development, if not world politics. How it came to be is known only to the few people involved. It is a great example of individual initiative, collective whimsy, serendipity, and unintended consequences.

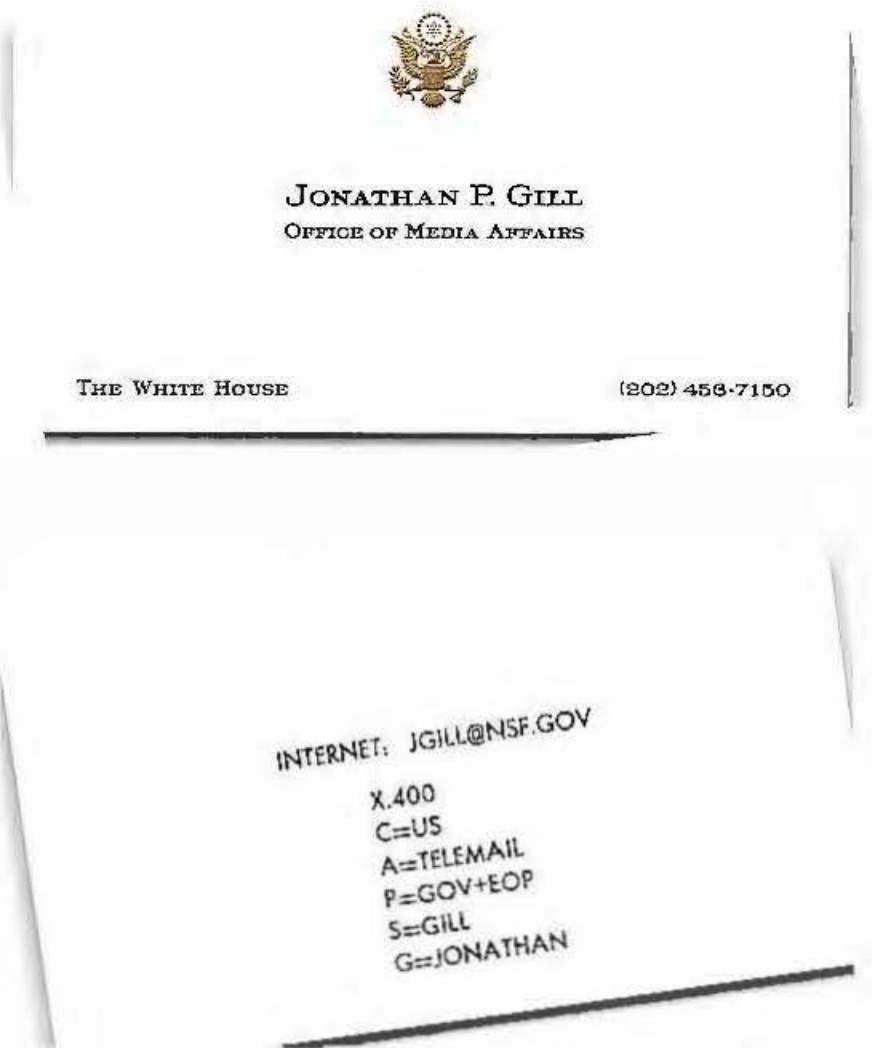

When Bill Clinton arrived at the White House on 20 January 1993, he brought with him a kind of rag-tag team who had helped him get there. One of the more notable was an energetic straight-talking entrepreneur from Vermont who passed out his simple White House business card—Jonathan P. Gill, Office of Media Affairs. Jock (as he was generally known) was everywhere, and began by demanding email access to the DARPA academic internet.

Meanwhile, early the previous year, Stu Mathison at Sprint International brought me to Reston, Virginia, from a senior position at the International Telecommunication Union in Geneva to help drive its internet business. Stu had previously helped network legend Larry Roberts to start up the world’s data networking business in the 1970s with the creation of the Telenet Corporation. He saw a rapidly growing market in positioning Sprint (which had acquired the Telenet assets re-named as Sprint International) as the global leader in combining its huge network of access ports, together with supporting and tying together all the different internets and applications at the time. Especially significant were two contracts. One was the NSF International Connections Manager which made Sprint the predominant global provider of DARPA internet backbone services. The second was Sprint’s award of half the FTS2000 contract with the White House as its customer.

Jock turned the White House into a high-profile demanding customer. The problem was that the White House—like all of the U.S. government, was committed to a secure OSI internet, and the only messaging capability from the White House internal network used the secure OSI X.400 platform originally developed via the NSA SDNS initiative. Jock wanted access to DARPA email. So Sprint—which had almost universal network platform arrangements among the many internets and applications—arranged to haul the X.400 messages on a slow packet network link up to Ann Arbor MI for MERIT to convert the messages and enable Jock’s DARPA Internet messaging.

Unfortunately, the lash-up was very slow, and at one point, Gill complained that “a snake could cross Pennsylvania Ave carrying the messages faster than Sprint’s service.” That image quickly caught the attention of Sprint executives. A series of events occurred.

The White House IT Director, Jack Fox, scheduled a meeting at his office around Thanksgiving 1993. He pulled together staff from around the Executive office of the President (EOP) to his office in the new Executive Office Building overlooking Pennsylvania Avenue to deal with “the problem.”

A few days before, the Urbana National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA)—which pioneered the Mosaic browser development - had just released for the first time, a Windows version of the browser that ran on my workstation. The WWW platform developed at CERN by Belgian engineer Robert Cailliau based on Ted Nelson’s hyperlink innovation was regarded as a relatively useless for the general public until two young students who loved writing code—Marc Andreessen and Eric Bina—effectively made the WWW platform feasible. Mosaic made the WWW platform viable if not compelling.

In the Autumn of 1993, my father visited and had obtained passes from his Congressman to visit the White House for the family. We also purchased several guidebooks. On the way into Washington on the Metro subway from Sprint’s Reston Virginia location to Fox’s meeting, the idea came to mind to create a website that was sketched out on the trip. It was based on the idea of allowing someone like my father to experience a virtual Whitehouse visit and facilitate access throughout the Federal government. There were three dimensions to the site sketch: 1) a national monument, 2) the seat of the executive branch, and 3) the home of the President.

After the meeting started in Fox’s office with many White House staff assembled to fix the email problem, he announced that the EOP had just purchased a then expensive T1 dedicated circuit to the DARPA internet from Sprint, and he asked everyone what the White House was going to do with it. After a very long pause, my virtual visit concept was sketched out on a whiteboard. Everyone loved it. Jack said, “why doesn’t Sprint build it.”

Upon returning to Sprint’s Reston offices, the news was ecstatically emailed to everyone up to the CEO of Sprint in Kansas City. The return message, however, was dismaying: “why would Sprint want to build/host websites.” I was on my own with just a home workstation.

Images from the guidebooks my father had purchased were scanned, and an initial prototype website was created. My young daughter Kelly contributed to the design, insisting that any White House site had to feature Socks the cat. It was transferred to a small Gateway Notebook and taken to a meeting with Jock and his staff. It was a go.

The next step was to reach out to a friend—Sun Microsystem’s ubiquitous, always available CTO, Eric Schmidt. He loaned out a couple of their new quad processor servers that were set up in an empty Old EOB room. Also needed was some programming/operations talent. Jock contacted Tony Villasenor at NASA. The EOP.GOV domain was registered on 10 Dec 1993 as “Executive Office of the President USA” by JSF.

There were ultimately two delays in the rollout. One was rather short-lived—finding photos and audio for Socks the cat. The other was the linking to other agencies—almost none of which had websites. For that, we ended up capturing the Federal Handbook index of agencies and manually checking which had sites up or not. A prototype White House website index page was assembled and printed in color for someone to hand out—allegedly by POTUS—to embarrass the many agencies without websites into getting Websites up. Those who didn’t have sites appeared a dull gray on the index. It took several months to get even a few of them online.

Finally, the WhiteHouse.GOV domain was registered on 17 Oct 1994 as “Whitehouse Public Access” by JSF, and the site went live to the world, complete with Socks and his meow. The effects were exponential, immediate, and global. The DARPA academic internet platform and its applications became dominant in the marketplace—significantly benefitting its proponents. The effects started rippling around the world. With the DARPA academic internet’s enormous inherent vulnerabilities, however, the threats to infrastructure and the fabric of society also went exponential—an unintended but profoundly adverse cybersecurity consequence that remains a major challenge today.

Jock Gill, near the end of Clinton’s first term, returned to Vermont to champion sustainable environmental innovations. Sprint largely moved away from the internet business only to reinvent its offerings as mobile access services and ultimately merge into T-Mobile. Eric Schmidt, after leaving Sun, became CEO at Novell and then Google. The article’s author continued to change careers every few years to stay on the cutting edge of new network technologies and deal with the never-ending internet threats. Kelly became a distinguished civil engineer in Dubai, and then returned to start up extraordinary, innovative web-based non-profits to save animals.

Sponsored byIPv4.Global

Sponsored byDNIB.com

Sponsored byWhoisXML API

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byCSC

Sponsored byRadix

Sponsored byVerisign

I had a similar experience with the Sprint CEO 4 years later when he canned the decision to buy most of the bankrupt MMDS (2.5-2.6ghz) companies nationwide for ownership or access/control to 80-160mhz of spectrum for a mere $2-3bn. He turned that down but after getting in a bidding war variously spent $4-5bn for only 40%. Years later when the company merged with Nextel the combined footprint was valued at $30bn. And today it’s the gem of T-Mobile’s renaissance.