|

||

|

||

A recent news story1, following research from security provider Infoblox, highlighted the case of the ‘Revolver Rabbit’ cybercriminal gang, who have registered more than half-a-million domains to be used for the distribution of information-stealing malware. The gang make use of automated algorithms to register their domains, but unlike the long, pseudo-random (‘high entropy’2, 3) domain names frequently associated with such tools, the Revolver Rabbit domains instead tend to consist of hyphen-separated dictionary words (presumably so as to obfuscate their true purpose), with a string of digits at the end. The majority of their domains (approximately 500,000, i.e. 500k) were hosted on the .bond TLD (top-level domain, or domain extension), but with around 200k more reported across other TLDs.

As an investigation into the scale and execution of the campaign, I first consider domains with names of the relevant format with the .bond extension. As of the date of analysis (22-Jul-2024), the .bond zone-file (providing a comprehensive list of all domains currently registered across the extension) was unavailable for analysis; however, data from a third-party source4 contained a similar number (actually slightly more) of .bond domains (385k) as DomainTools’5 estimate of the total number registered across the extension (377k), and was therefore used instead for this study.

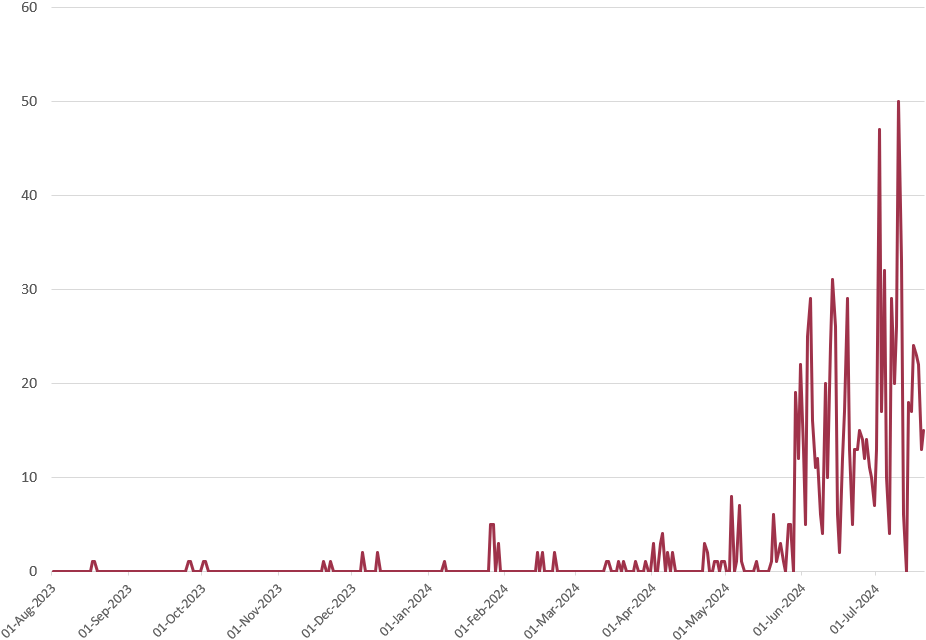

The study considers all .bond domains containing (at least) two hyphens, with the second hyphen immediately followed by a numerical digit6. This yields a dataset of just over 280k domains (actually over 70% of all domains registered on the TLD), and perhaps (in view of the previously reported estimate of 500k domains) suggests that a significant number of additional domains registered for use in the campaign may subsequently have lapsed. In order to provide an overview of the key features of the domains, I next consider a sample of 1,000 of these domains (actually the first 1,000 alphabetically). They show a number of features in common, including repeated use of the same registrars (with Key-Systems accounting for 985, and NameCheap for 15) and registrants (with registrant e-mail addresses @domain-contact.org given in 864 cases, @key-systems.net in 121, and @uptakeleads.com, @namecheap.com, and @withheldforprivacy.com in the remainder), and registration (domain creation) dates all within a relatively narrow time window (with 897 (89.7%) of the domains registered in the period since 29-May-2024, also noting that the most recent registration date was 20-Jul-2024, indicating that the campaign was likely still ongoing as of the date of analysis). These types of insights are key to the ability to ‘cluster’ together findings and establish likely connections between them7.

At the time of the study, none of these domains resolved to any significant content other than pages of pay-per-click (PPC) advertisements, presumably emplaced as a means of monetising the domains—whose purchase has potentially involved an investment of over $1 million—between periods of alternative use. The lack of any more meaningful site content suggests either that the malware distribution takes place from ‘deeper’ pages of the sites, or that the domains may be utilised only for short periods of activity and are now either dormant or pending activation. There is also a suggestion from previous research that the majority of the domains may have been registered as ‘decoys’ to mask the small number of active examples.

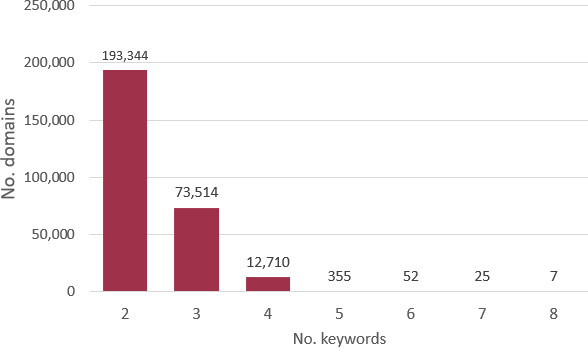

Returning to the full set of 280k .bond candidate malware domains, the data actually shows a range of domain-name structure patterns, featuring examples with between 2 and 8 distinct strings (keywords) separated by hyphens (Figure 2). The longest identified domain containing 8 keywords—which may not necessarily be part of the Revolver Rabbit cluster—is es-sicily-and-south-of-italy-tour-packages-27j.bond.

The dataset also features a number of ‘sub-clusters’, in which the same keyword pairs are used multiple times. The top ten most frequently occurring pairs are shown in Table 1.

| String | No. instances |

|---|---|

| dental-implants | 8,130 |

| car-deals | 4,401 |

| development-training | 3,958 |

| influencer-marketing | 3,854 |

| design-courses | 3,333 |

| warehouse-inventory | 3,040 |

| systems-panels | 2,837 |

| air-condition | 2,752 |

| warehouse-services | 2,735 |

| electric-cars | 2,545 |

In these cases, the sub-clusters tend to feature domains where (only) the numerical string differs between the various examples; the first five ‘dental-implants’ domains (for example) are alphabetically: dental-implants-001.bond, dental-implants-01.bond, dental-implants-02.bond, dental-implants-024.bond, and dental-implants-0243.bond.

Next, it is informative to widen out the search across other gTLDs for which zone-file information is available, to determine how many domains with names of the same format appear across these other extensions. This search actually reveals over 354k more domains, for which the top twenty most frequently occurring domain extensions are shown in Table 2.

| TLD | No. domains |

|---|---|

| com | 72,054 |

| today | 51,504 |

| med | 39,498 |

| xyz | 30,193 |

| fyi | 17,769 |

| info | 16,919 |

| live | 15,097 |

| world | 13,968 |

| zone | 12,304 |

| online | 10,902 |

| click | 9,925 |

| shop | 9,153 |

| space | 9,094 |

| net | 7,838 |

| site | 7,437 |

| top | 5,015 |

| org | 2,970 |

| buzz | 2,922 |

| fun | 1,505 |

| store | 1,468 |

Outside the group of TLDs within the table which are popular generally, it is striking that this list contains many new-gTLD extensions which have previously been noted as being associated with high rates of infringement and abuse, due to factors such as the ease and cost of registrations, and provider security policies8. For example, seven of the top-ten gTLDs found by Spamhaus to have the greatest rates of association with malware9 appear also in the list in Table 2.

Overall, this analysis suggests that over 600k domains potentially associated with the Revolver Rabbit malware distribution campaign are still actively registered, together with others which may have been used previously and subsequently allowed to lapse. Given the costs of domain registrations, this suggests a substantial financial investment on the part of the cybercriminals, and provides an indication of the amount of revenue these malware campaigns may be able to generate, through the utilisation and sale of stolen credentials—in addition to any further profits which may be available through domain monetisation processes, such as the inclusion of PPC links on the sites.

The findings also provide an indication of the importance of brand-protection programmes encompassing both monitoring and enforcement—specifically in cases where particular brands or company customer bases are targeted. This particular case study highlights the difficulty in proactively monitoring for criminal activity (or other abuse) in cases where there are (for example) no specific strings (such as brand names) to monitor for in the infringing domain names. In these instances, it is necessary to make use of other domain-name characteristics, which are often less diagnostic or more ‘fuzzy’ in nature—such as shared registration details or similar domain-name structures or keyword patterns—which, when considered together, can identify links between otherwise apparently unrelated findings and establish the existence of ‘clusters’ of associated results.

Sponsored byDNIB.com

Sponsored byWhoisXML API

Sponsored byRadix

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byIPv4.Global

Sponsored byCSC

Sponsored byVerisign