|

||

|

||

A Quiet Erosion of RIR Legitimacy?

Legality was observed. Legitimacy was not.

For more than two decades, global Internet Governance has rested on a deliberate equilibrium: technical coordination without political capture, community authority without governmental override, and institutional legitimacy grounded in law and the process as well.

The Regional Internet Registry (RIR) system embodies this balance. Its authority does not derive from states, donors, or intergovernmental endorsement, but from bottom-up participation, operational independence, and adherence to globally consistent principles, most notably those articulated in ICP-2: Criteria for Establishment of New Regional Internet Registries.

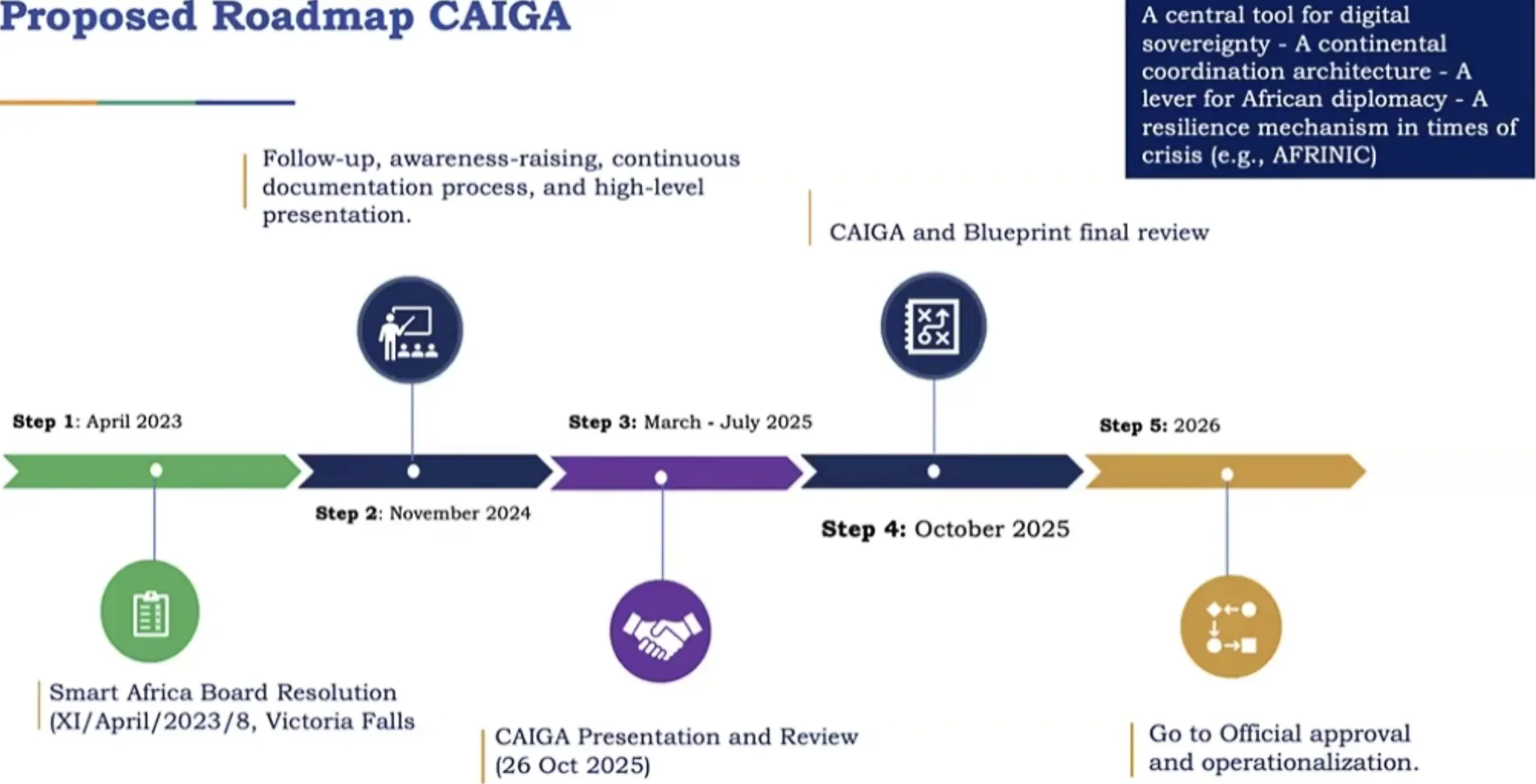

It is against this backdrop and the signed MOU that ICANN’s involvement with Smart Africa’s Internet Governance Blueprint and the associated proposal for a “Council of African Internet Governance Authorities” (CAIGA) warrants careful, dispassionate examination.

This argument is about process, signaling, and institutional responsibility, not intentions.

Governance concepts associated with the Smart Africa Internet Governance Blueprint circulated in international forums prior to their appearance in broader regional discussions.

At ICANN82, February 2025, Smart Africa Reported during a Governmental Advisory Committee (GAC) Africa regional session, A “key initiative” that “includes but is not limited to”:

The report also included: Regulatory coordination under the Smart Africa framework, developments concerning AFRINIC, monitoring of AFRINIC’s electoral process, commission of an ad-hoc committee, and participation of GAC representatives in groups associated with the ICP-2 review process. These discussions took place in a governmental and regulatory context and did not involve structured consultation with the AFRINIC membership or the publication of governance-impact documentation. I didn’t find a public record for the “African Regulatory Council” meeting that was referred to in the opening report.

Subsequently, April 2023 Smart AFRICA announced an “extraordinary meeting on AFRINIC reforms” and the “toolkit” came out whereby the candidates’ list was shortened. This statement was smartly added to the announcement “Building on key recommendations from #ICANN82 and the African Regulatory Council, the meeting will provide legal updates, mobilize Member State support, and outline concrete actions ahead of the AFRINIC elections on June 23, 2025.”

During ICANN83 in Prague, May 2025, Smart Africa convened meetings at the sidelines of the ICANN meeting week. Publicly circulated agendas for those meetings included a GAC Africa session listing items titled “Blueprint Implementation Progress” and “Agreement on the creation of CAIGA.” Other related sessions referenced in that context, the 11 June 2025 Smart Africa Internet Governance Working Group, do not appear in ICANN’s publicly accessible meeting schedules or archives. A significant item on the agenda of 11 June 2025 is “Finalization of CAIGA documents for official Launch at TAS2025.”

Across these forums, and from available resources, there were reasonably no recorded public objections or recorded community alarms regarding the governance implications of CAIGA or the Blueprint appear in the contemporaneous public record.

According to the presenter, speaking about the blueprint, “From our perspective ICANN is coming together with SMART AFRICA, ... Smart Africa is backed by the prime ministers and presidents across Africa, so there is a tremendous of political mass of political force this time around, this should not be of course a paper tiger, this is about implementation, this is not an academic project, this is a practical project backed by the political leadership of Africa”. Minutes 35-39

The governance implications of the “Blueprint” and “CAIGA” became visible to AFRINIC community participants during the Africa Internet Summit (AIS) in Accra, where Smart Africa organized a meeting on the sidelines of the summit in September-October 2025.

Access to documentation was facilitated through the documentation, and links were shared directly with participants from the meeting Minutes. The absence of contemporaneous public records from that session delayed broader community awareness and constrained informed scrutiny of the proposals under discussion.

This moment marked a procedural inflection point: governance concepts that had circulated earlier in governmental and ICANN-adjacent settings surfaced in a regional context directly affecting the RIR community, without having passed through established bottom-up consultation pathways.

On 18 November 2025, ICANN published a blog post titled ”ICANN’s Commitment to the Africa Community.” In it, ICANN described its role in the Smart Africa initiative as follows:

“ICANN provided financial and administrative support for the development of the IG Blueprint… This does not equate to ownership or responsibility for the content.”

The post further stated that:

“ICANN did not endorse, own, or take responsibility for the Blueprint’s content or the CAIGA governance structure built upon it.”

In a subsequent letter dated 24 November 2025 to the Chair of ICANN’s Non-Commercial Stakeholder Group (NCSG), ICANN reiterated this position and added:

“ICANN did not enter either the MoU or the Project Agreement with the intention that the IG Blueprint would propose a new governance model for the RIR serving the region of Africa and the Indian Ocean.”

ICANN also acknowledged that:

“As currently set out in the IG Blueprint, it is not clear to ICANN that the CAIGA proposal meets [ICP-2] requirements.”

“The CAIGA proposal is embedded into the IG Blueprint draft that Smart Africa commissioned. Smart Africa is one of the partners to the Coalition for Digital Africa (CDA). As I explained in my 18 November 2025 blog on ICANN’s Commitment to the Africa Community, ICANN and Smart Africa are parties to a Memorandum of Understanding, as well as to Project Agreement through which ICANN committed $40,000 for Smart Africa to develop a reference document—the IG Blueprint—that sets out a long-term vision and roadmap for Internet governance in Africa.”

Taken together, these statements establish ICANN’s legal posture with clarity: funding without ownership, engagement without endorsement, and neutrality with respect to the resulting governance proposal.

What they do not resolve is the question of legitimacy, joint work, and “why Africa”?

ICANN has publicly confirmed that it entered into a Memorandum of Understanding with Smart Africa in 2024, followed by a Project Agreement under which the IG Blueprint was developed, and that it contributed USD 40,000 toward that work. ICANN has also acknowledged participation in Smart Africa and Coalition for Digital Africa activities related to Internet governance capacity building, including appearances in GAC-related and Smart Africa–organized sessions at ICANN meetings.

At the same time, ICANN maintains that it:

“did not contract for or participate in CAIGA’s development.”

This distinction, between the IG-Blueprint and CAIGA, is legally precise; however, it is also governance-fragile.

CAIGA is presented by its proponents as an implementation architecture arising from the IG-Blueprint, and a joint work. The two are functionally linked in public presentation and political signaling, even if separable in contractual terms.

The final reform advisory report, states:

”9. Document Development ... The Ad-Hoc Committee produced .... A revised Bylaws document reflecting updated governance and operational provisions to be submitted to the Annual General Members Meeting (AGMM) for adoption. .... Proposals for the establishment of diplomatic immunities and legal protections. ..... Pending AGMM approval, these documents may be advanced for endorsement at the upcoming Smart Africa Heads of State Summit, framing continental political support.”

When an institution with ICANN’s symbolic and operational authority funds and participates in a process that produces governance proposals affecting an RIR, without prior evaluation of governance implications or early community consultation, the resulting legitimacy gap cannot be remedied by post-hoc disclaimers alone.

ICANN has not stated that CAIGA complies with ICP-2, and ICANN has not stated that CAIGA violates ICP-2. Instead, ICANN has taken the position that ICP-2 compliance is a matter for “the community” to determine.

Yet ICP-2 is not an abstract aspiration. It is the criteria document under which RIRs are recognized and sustained within the ICANN ecosystem. Its purpose is to ensure bottom-up governance, independence from political authority, and accountability to the Internet community rather than to states.

A framework that proposes political endorsement as an alternative to member ratification, intergovernmental oversight mechanisms, or paid participation structures raises immediate compatibility questions under ICP-2 on its face.

Declining to assess those questions while having funded and supported the process that generated them leaves a gap in institutional boundary maintenance.

ICANN has correctly noted that its Memorandum of Understanding with Smart Africa was published. What remains unresolved on the public record is equally material: the Project Agreement under which the IG-Blueprint was developed; AFRINIC members were not informed or consulted during the Blueprint’s development through the member-list or public records; knowing that CAIGA has an operational email [email protected] which circulated emails to the members of afrinic on August 19, 2025 a breach that was not explained but ignored. The Virtual meeting called for had a significant item: “Sharing updates on the official launch of CAIGA at ICANN84 “, a consultation after the fact, and another email also on September 9, 2025 regarding candidates list endorsed by Smart Africa.

Smart Africa also sent an email to apparently all AFRINIC members on August 13, 2025, with an invitation to an online consultation on the AFRINIC election and the CAIGA FRAMEWORK, exposing all members’ email addresses, with no explanation for this breach or how they obtained the list. No further invitation came in.

Reasonably, governance implications became visible to the community only after conference and side-meeting presentations, and some sessions central to the evolution of CAIGA lack publicly accessible documentation.

In multistakeholder governance, transparency is not a retrospective courtesy. It is a precondition of legitimacy.

In its correspondence with the NCSG, ICANN suggested that if communities wish to allow greater governmental involvement in RIR governance, “now is the time” to raise such proposals in the ongoing ICP-2 review process.

Subsequent references to, presentations of, CAIGA and the Internet Governance Blueprint have continued to appear in governmental and ICANN-adjacent settings (GAC). Materials and agenda items associated with later Governmental Advisory Committee (GAC) discussions at ICANN84, as well as references made in connection with regional telecommunications and digital governance forums in Guinea (TAS), indicate that the Blueprint and CAIGA were treated as ongoing initiatives with anticipated milestones and public communication timelines. These references occurred without any corresponding public reset of process, clarification of governance scope, or structured consultation with the AFRINIC membership, reinforcing concerns that procedural alignment lagged behind institutional momentum.

This framing matters.

ICP-2 exists precisely to constrain political intervention and preserve parity across regions. Introducing intergovernmental governance models into that process, after politically framed proposals have already circulated, risks transforming a technical safeguard into a negotiation arena.

Such a precedent would not remain confined to Africa.

ICANN has acted within the letter of its agreements. Whether its actions align with its stated commitments to bottom-up, community-driven governance remains an open question.

By funding and participating in a process that produced governance proposals affecting an RIR, while declining to assess their compatibility with ICP-2, ensure early community consultation, or provide full transparency, ICANN has exposed a structural weakness in how institutional boundaries are maintained.

If this IG-BluePrint with its product CAIGA is implemented, this wouldn’t be an African problem; it would become a global Internet governance problem.

The question now is not whether these outcomes were intended, but whether the governance lessons they reveal will be acknowledged, before precedent hardens into doctrine.

As ICANN shut the door to private communication, the only way that remains valid is public communication.

References (Public Record)

Sponsored byRadix

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byIPv4.Global

Sponsored byWhoisXML API

Sponsored byDNIB.com

Sponsored byVerisign

Sponsored byCSC